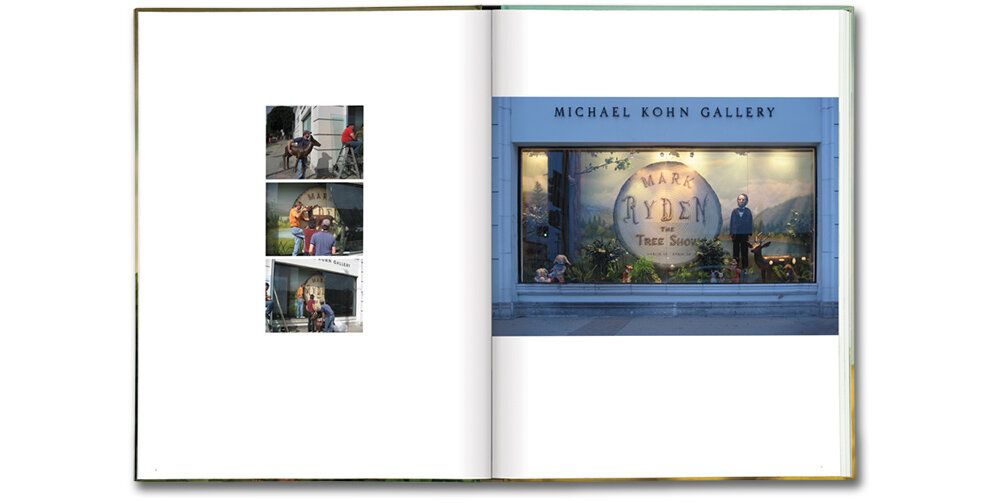

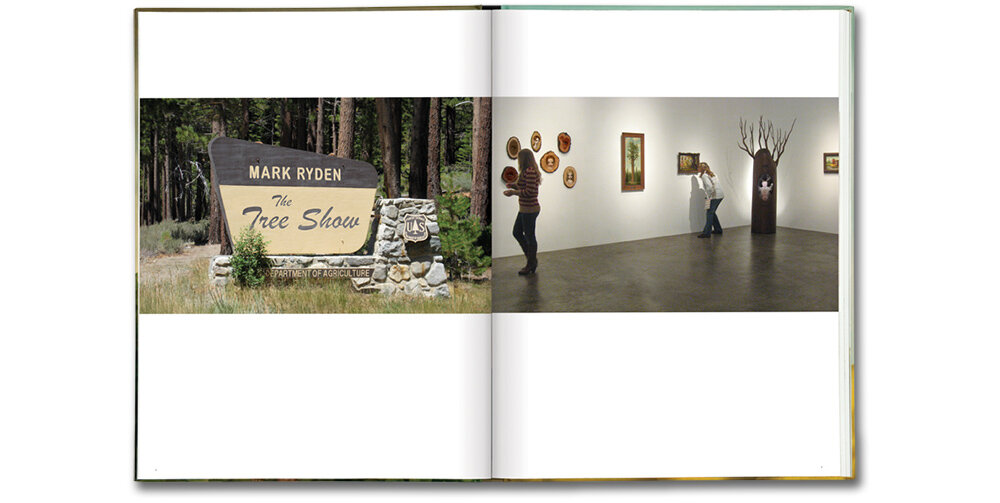

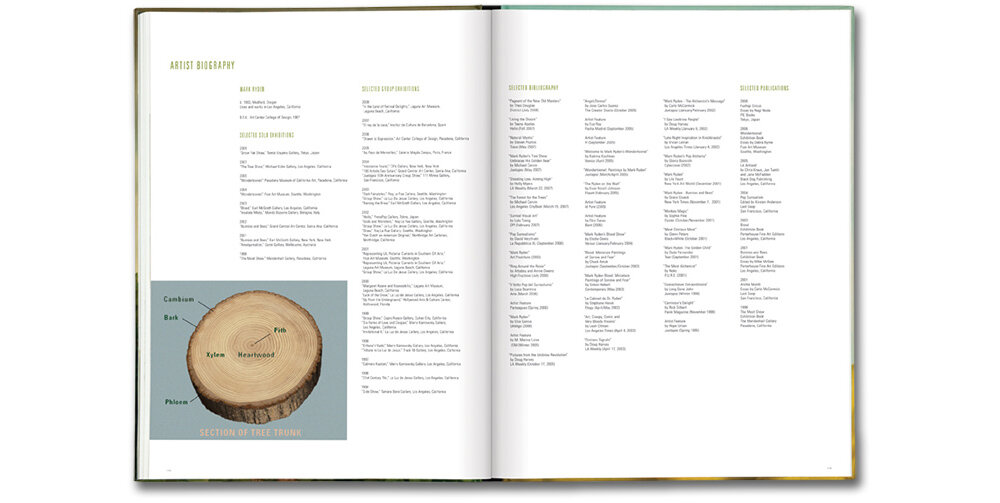

The Tree Show Exhibition Book

Publisher: Porterhouse Fine Art Editions

"Mark Ryden's Return to Nature"

Essay by Holly Myers

2009

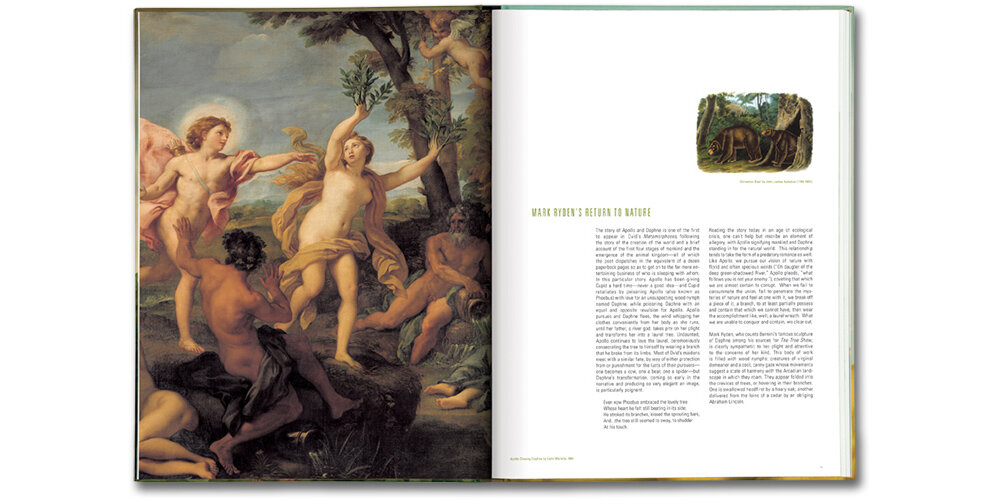

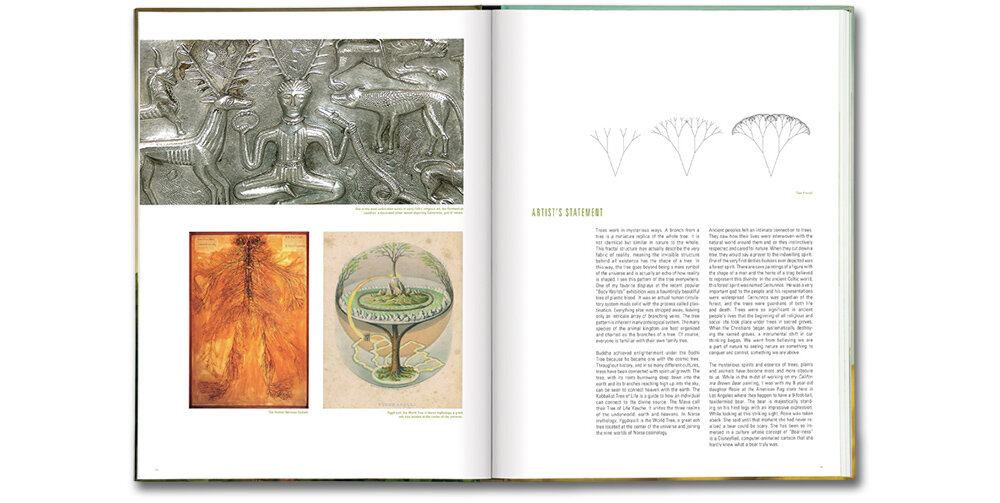

The story of Apollo and Daphne is one of the first to appear in Ovid's Metamorphoses, following the story of the creation of the world and a brief account of the first four stages of mankind and the emergence of the animal kingdom-all of which the poet dispatches in the equivalent of a dozen paperback pages so as to get on to the far more entertaining business of who is sleeping with whom. In this particular story, Apollo has been giving Cupid a hard time-never a good idea-and Cupid retaliates by poisoning Apollo (also known as Phoebus) with love for an unsuspecting wood nymph named Daphne, while poisoning Daphne with an equal and opposite revulsion for Apollo. Apollo pursues and Daphne flees, the wind whipping her clothes conveniently from her body as she runs, until her father, a river god, takes pity on her plight and transforms her into a laurel tree. Undaunted, Apollo continues to love the laurel, ceremoniously consecrating the tree to himself by wearing a branch that he broke from its limbs. Most of Ovid's maidens meet with a similar fate, by way of either protection from or punishment for the lusts of their pursuers-one becomes a cow, one a bear, one a spider-but Daphne's transformation, coming so early in the narrative and producing so very elegant an image, is particularly poignant:

Even now Phoebus embraced the lovely tree

Whose heart he felt still beating in its side;

He stroked its branches, kissed the sprouting bark,

And... the tree still seemed to sway, to shudder

At his touch.

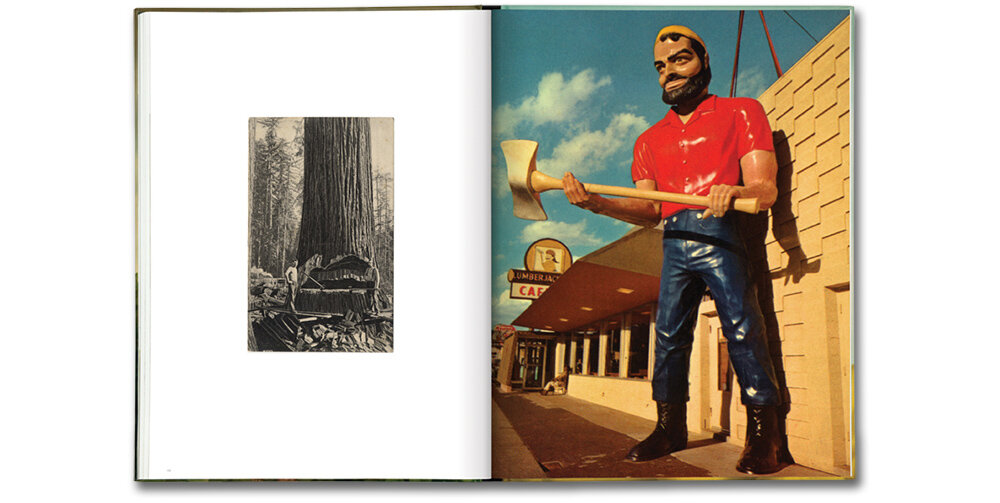

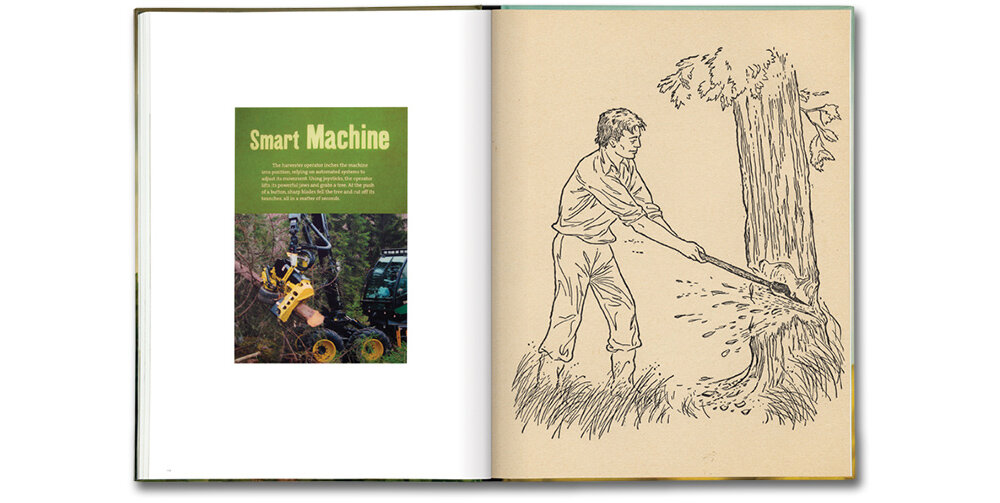

Reading the story today in an age of ecological crisis, one can't help but inscribe an element of allegory, with Apollo signifying mankind and Daphne standing in for the natural world. This relationship tends to take the form of a predatory romance as well. Like Apollo, we pursue our vision of nature with florid and often specious words ("Oh daughter of the deep green-shadowed River," Apollo pleads, "what follows you is not your enemy."), coveting that which we are almost certain to corrupt. When we fail to consummate the union, fail to penetrate the mysteries of nature and feel at one with it, we break off a piece of it, a branch, to at least partially possess and contain that which we cannot have, then wear the accomplishment like, well, a laurel wreath. What we are unable to conquer and contain, we clear-cut.

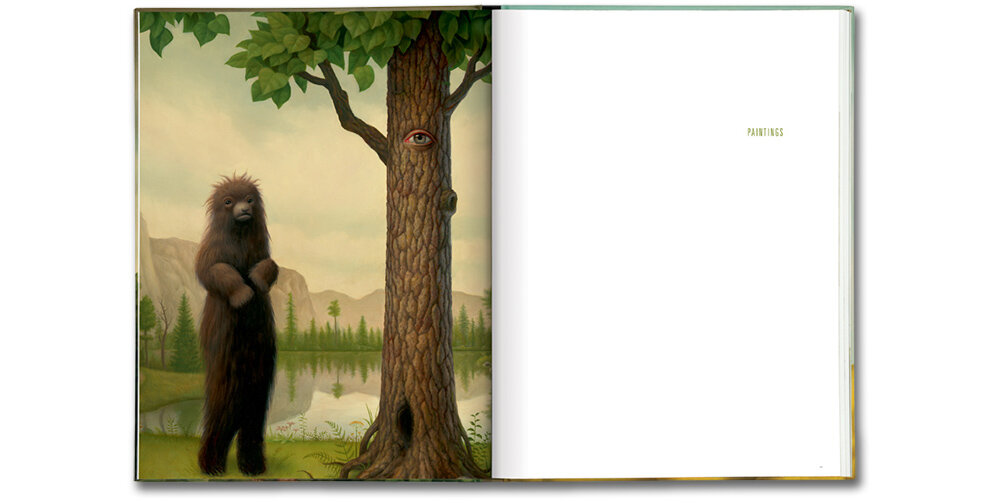

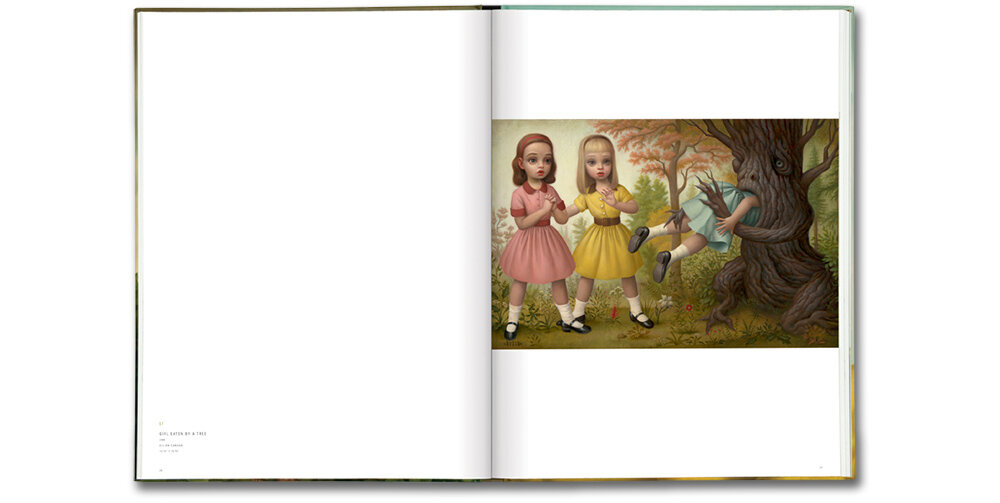

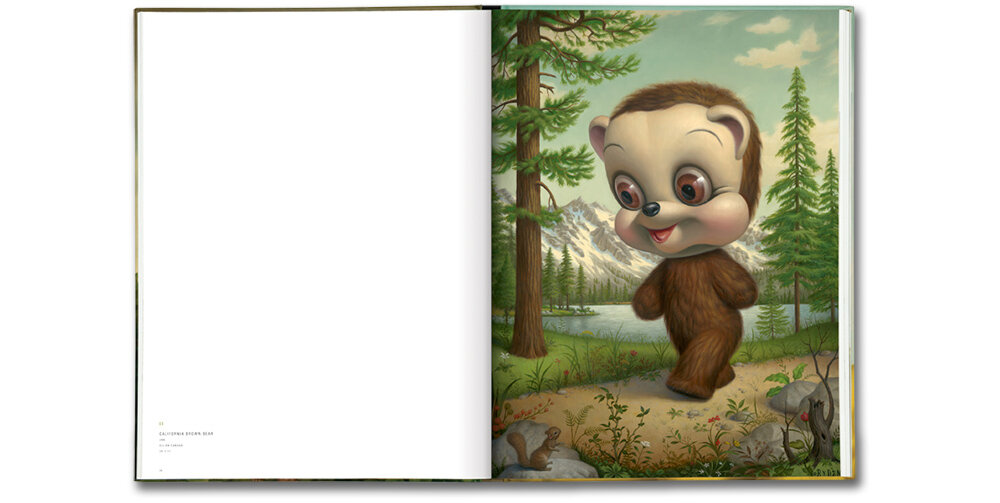

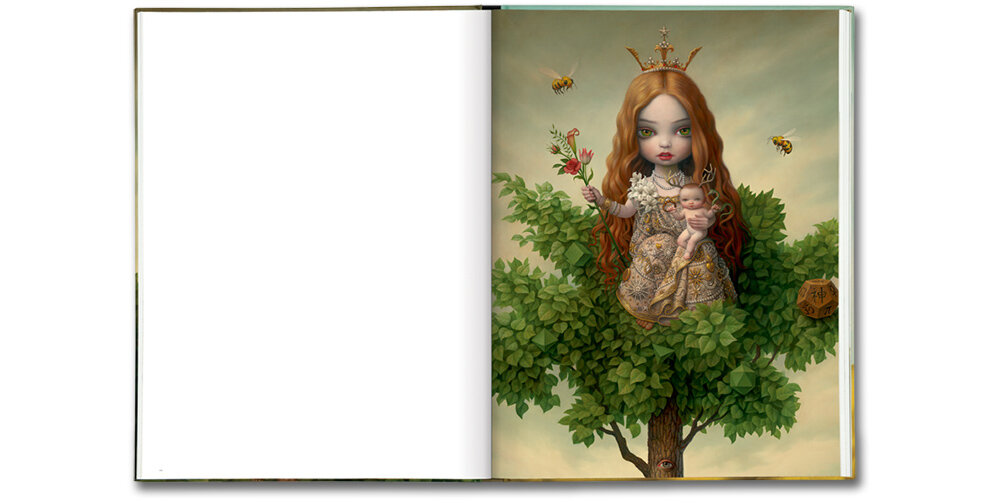

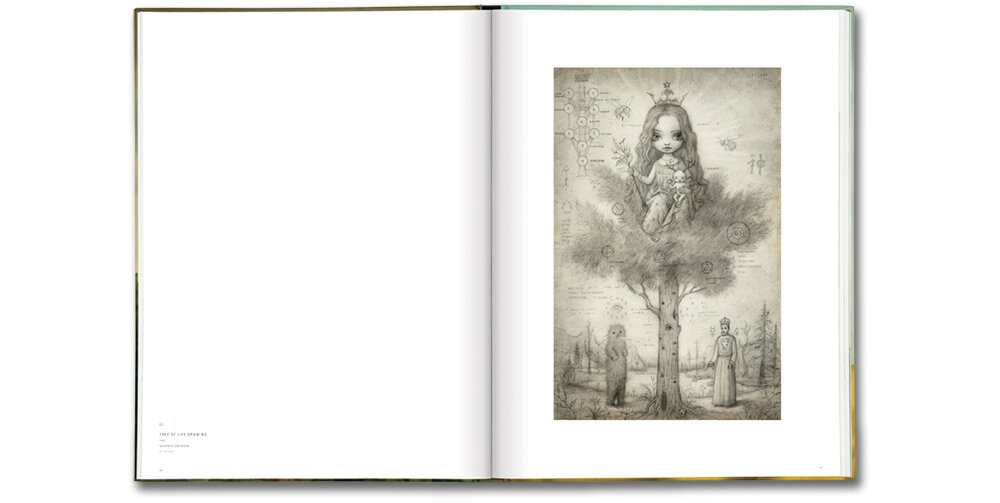

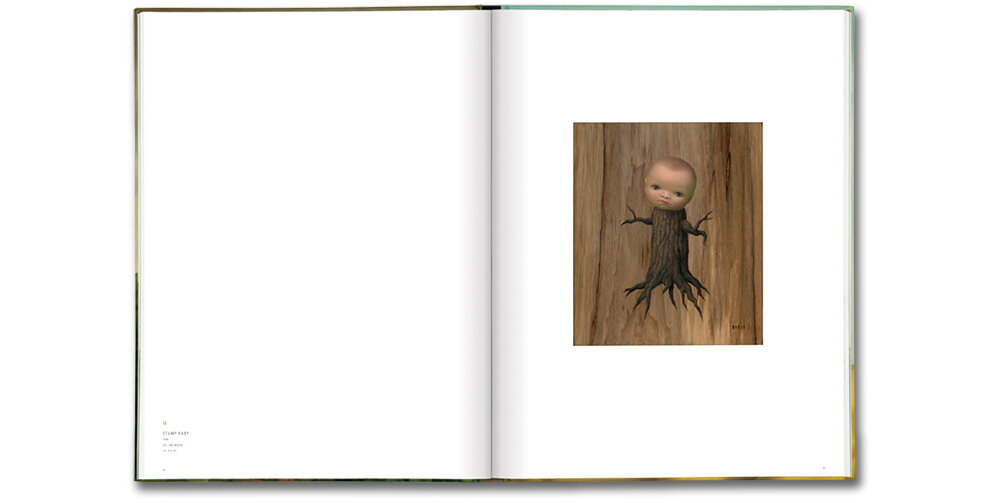

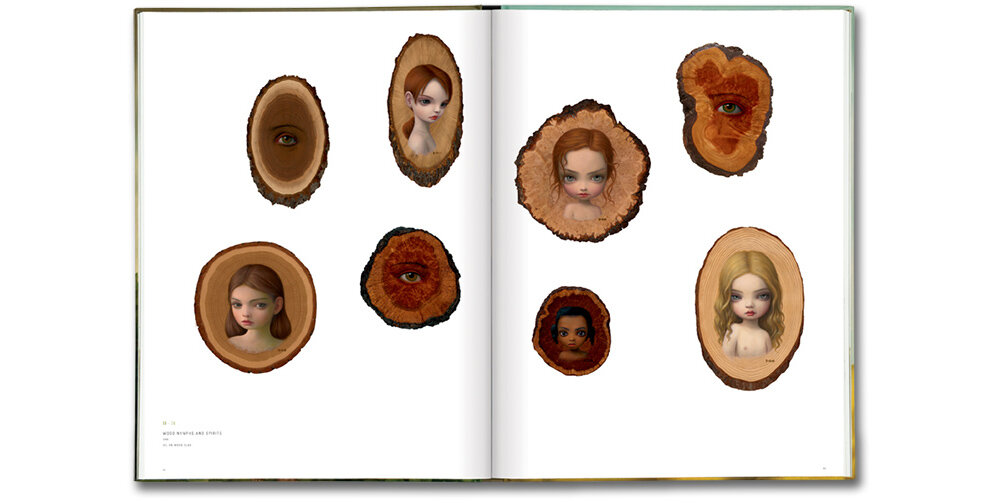

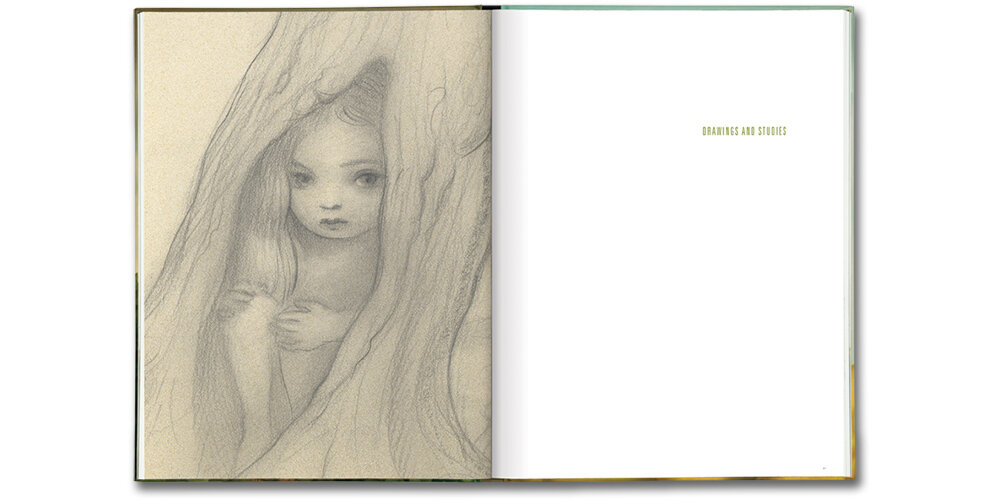

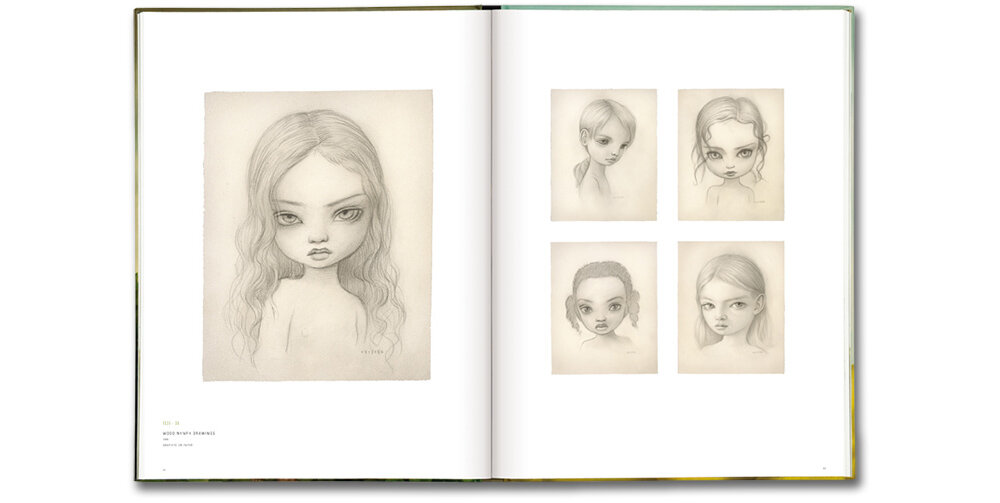

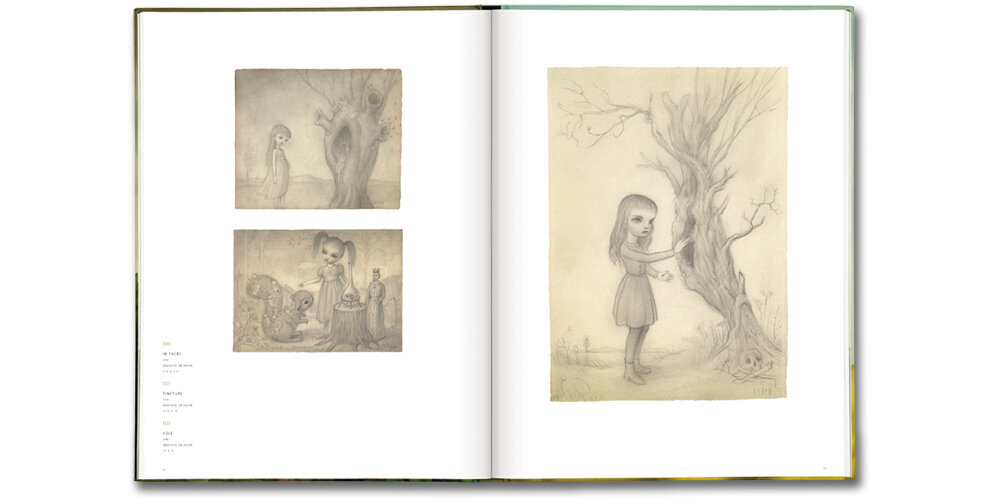

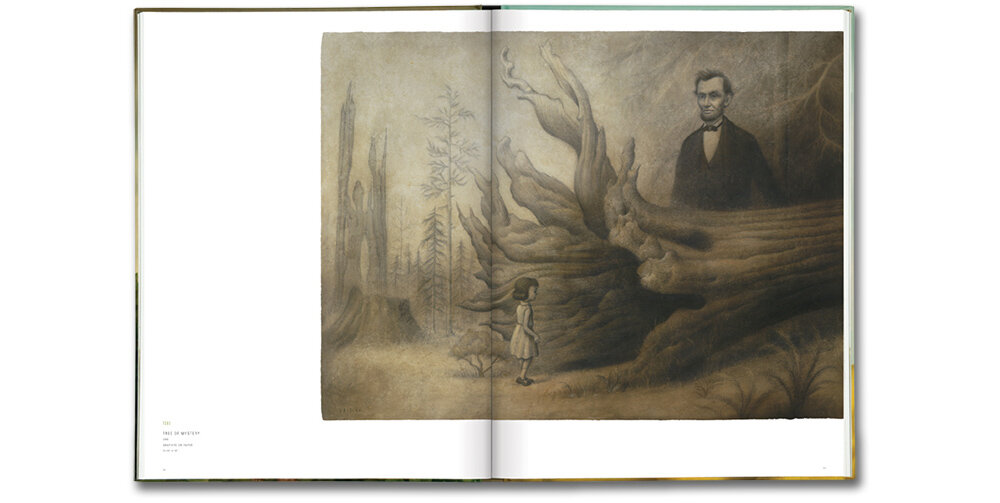

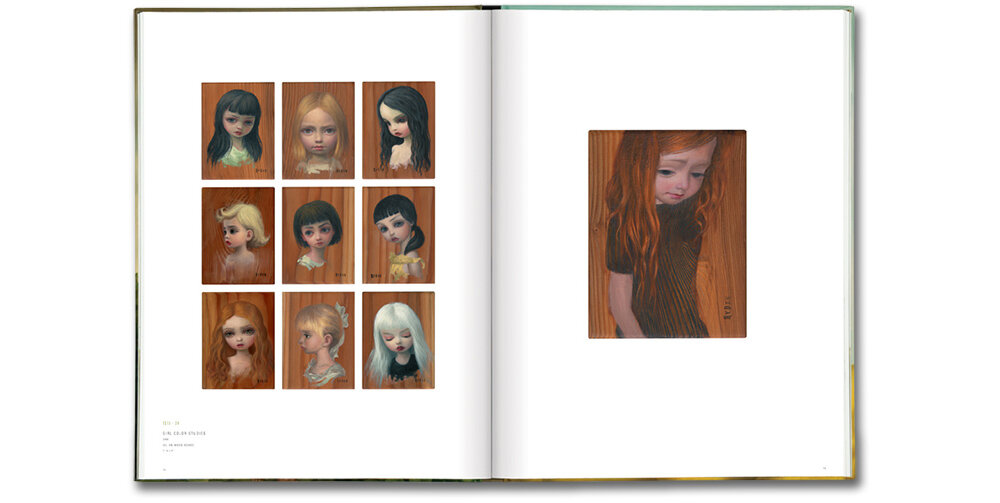

Mark Ryden, who counts Bernini's famous sculpture of Daphne among his sources for The Tree Show, is clearly sympathetic to her plight and attentive to the concerns of her kind. This body of work is filled with wood nymphs: creatures of virginal demeanor and a cool, canny gaze whose movements suggest a state of harmony with the Arcadian landscape in which they roam. They appear folded into the crevices of trees, or hovering in their branches. One is swallowed headfirst by a hoary oak; another delivered from the loins of a cedar by an obliging Abraham Lincoln.

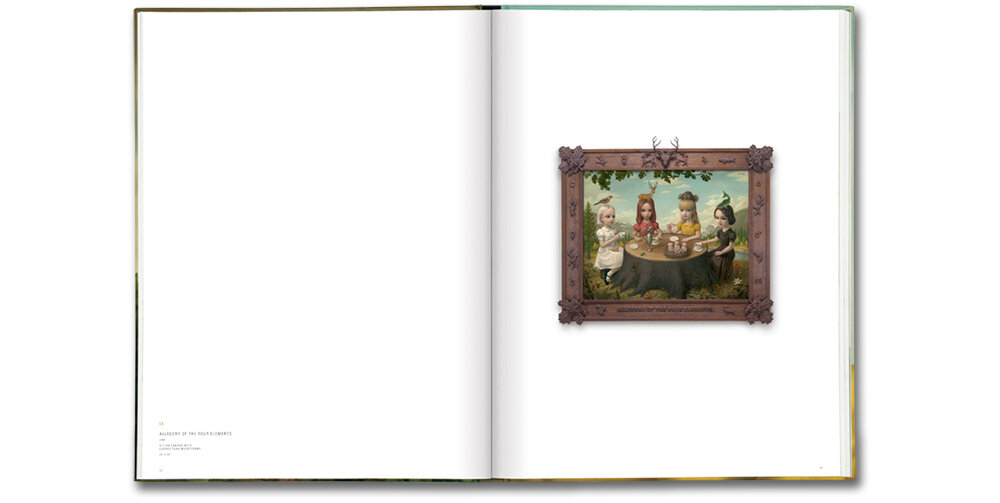

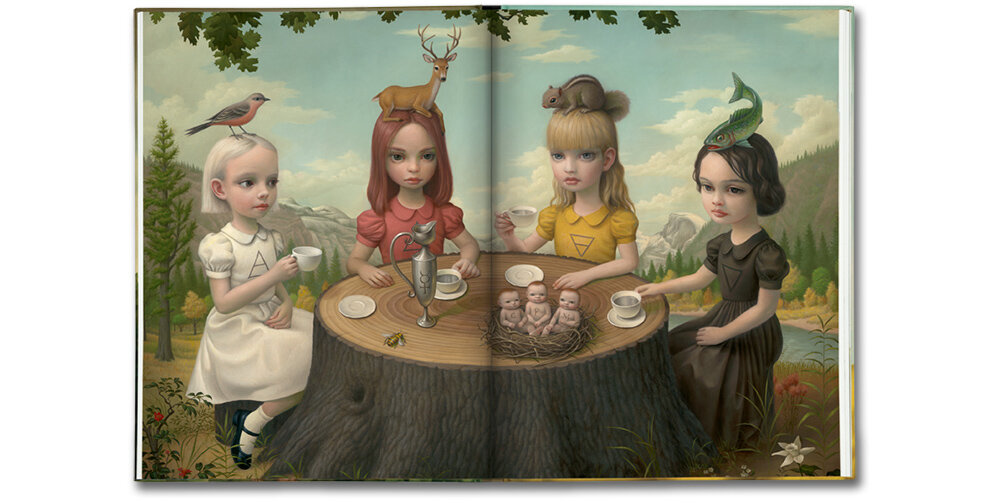

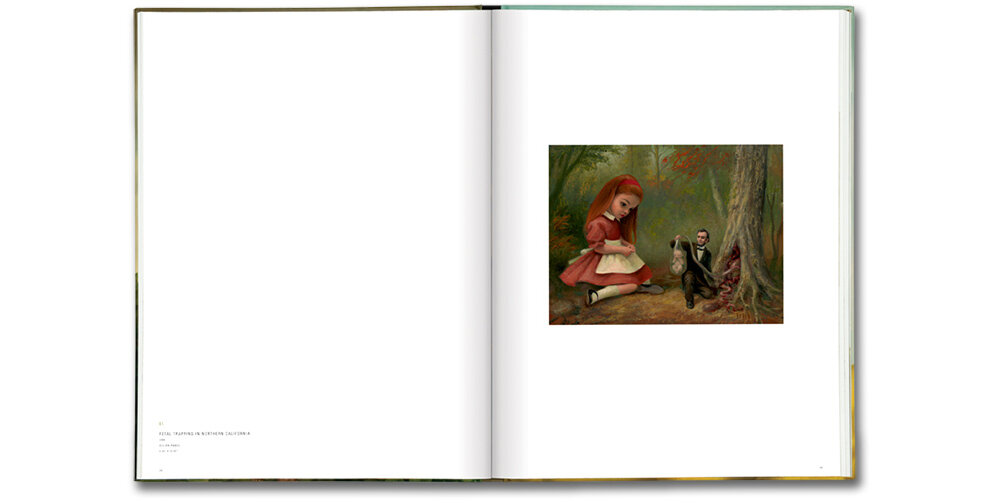

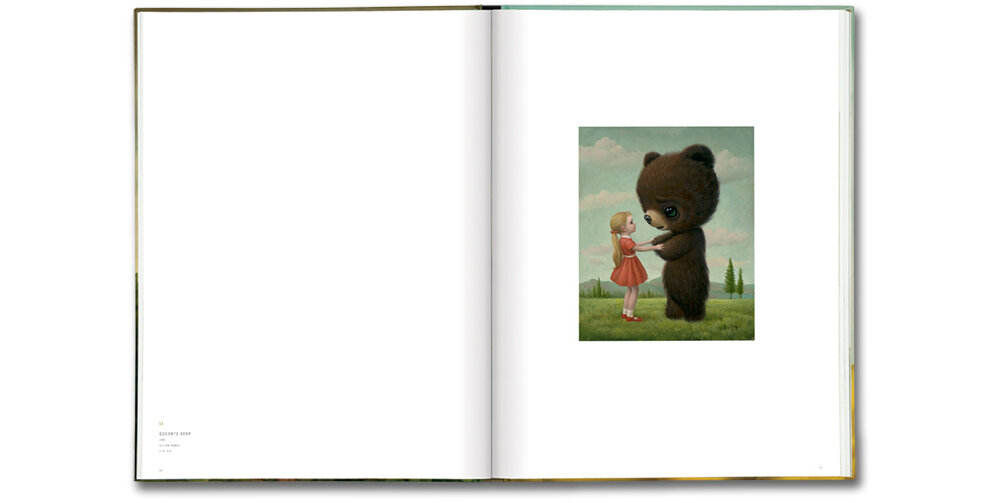

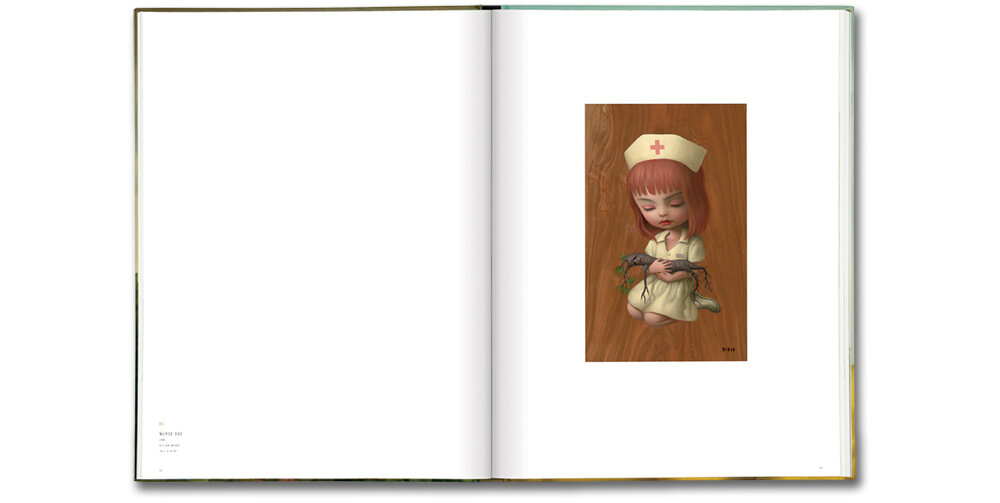

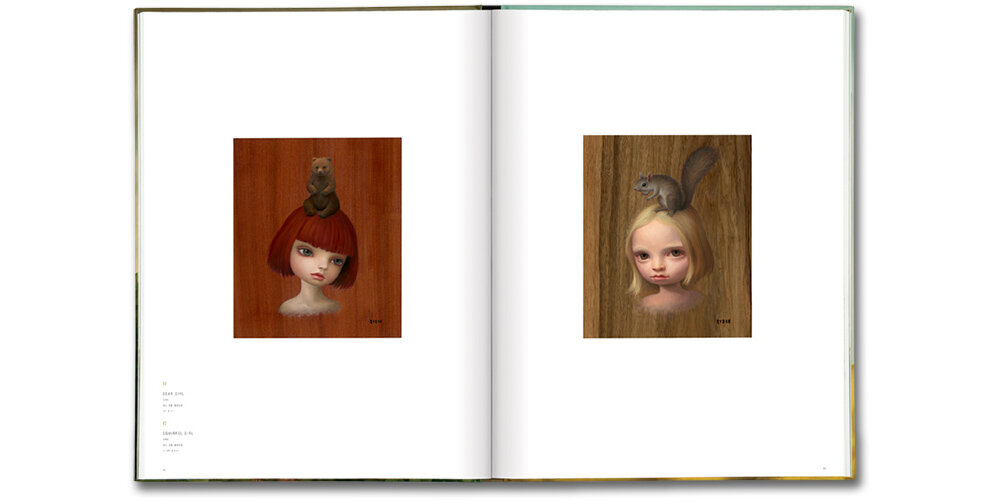

In Allegory of the Four Elements, one of the most enchanting works the artist has yet produced, four of these nymphs gather around a tree stump with an air of ethereal poise, as if holding the energetic currents of the world in balance. Though kin to the sultry, wide-eyed waifs who've populated Ryden's work for years, these creatures have a slightly different air: younger, milder, less eroticized. They don't tend to regard the viewer. Unlike most of the damsels in his last gallery show, the tellingly titled "Blood: Miniature Paintings of Sorrow and Fear," they bear no visible wounds. Indeed, if that show was, as Ryden professed in interviews at the time, an exploration of trauma, grief and loss, this show, by contrast, is all about life. The only trace of blood you'll find here is in the Abe Lincoln birth scene.

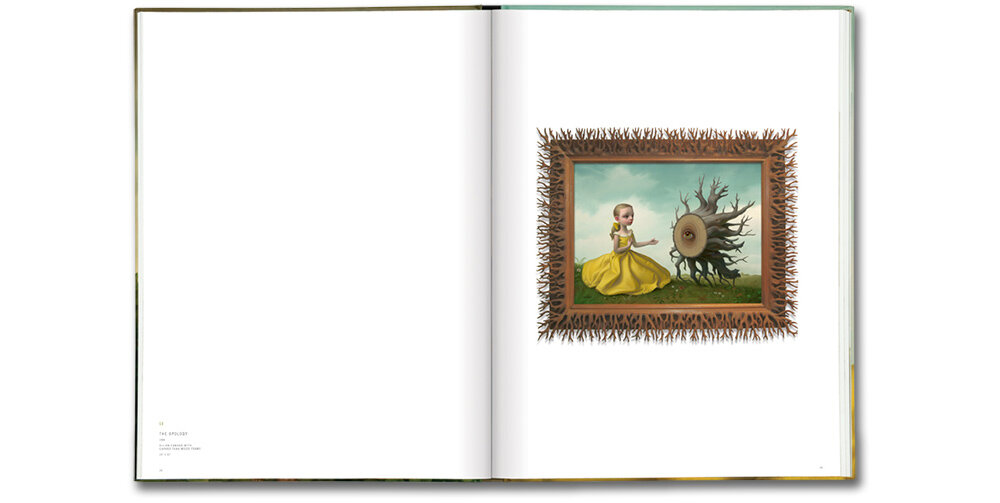

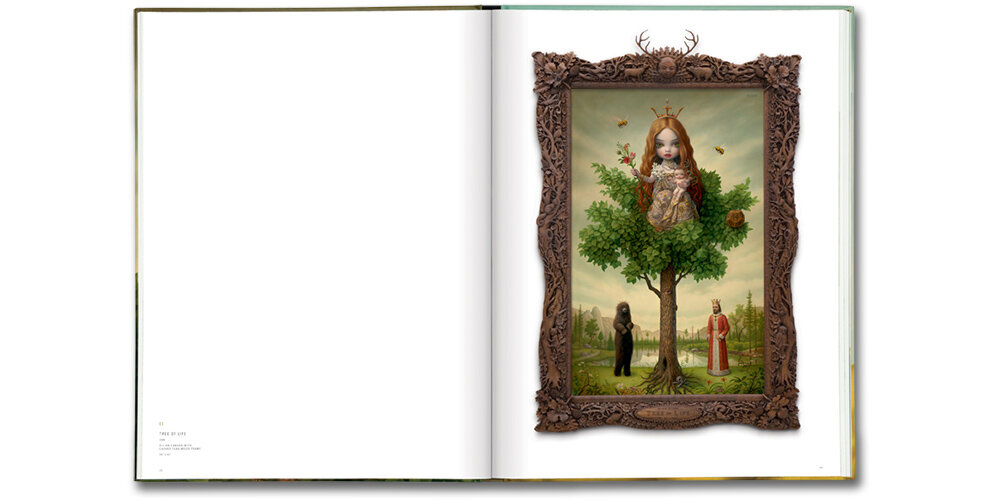

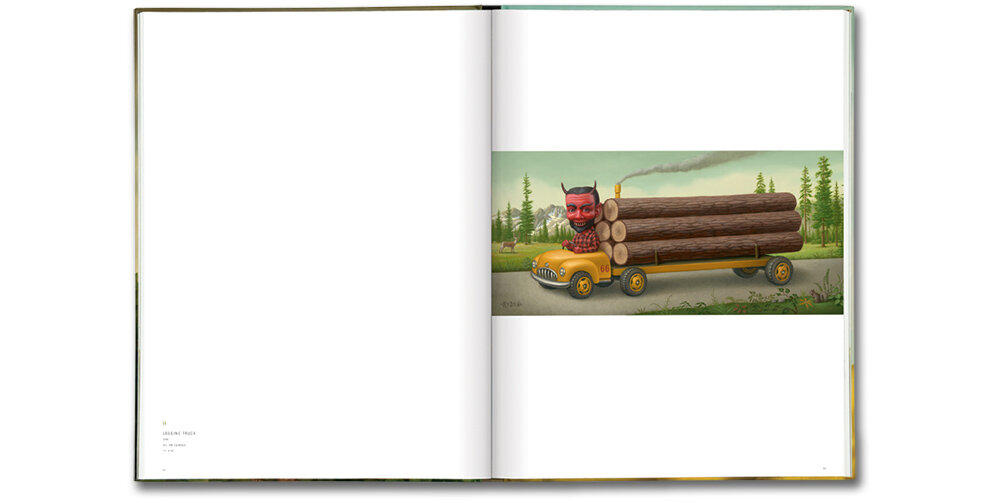

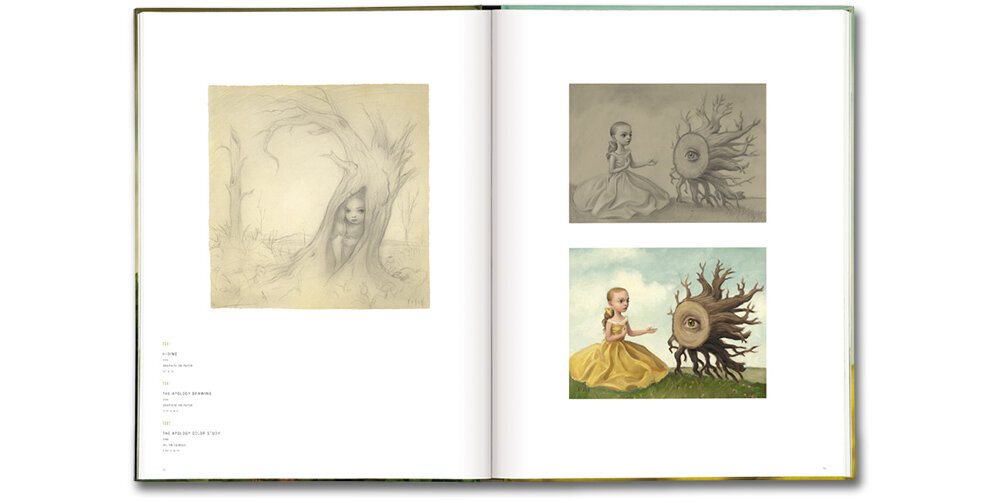

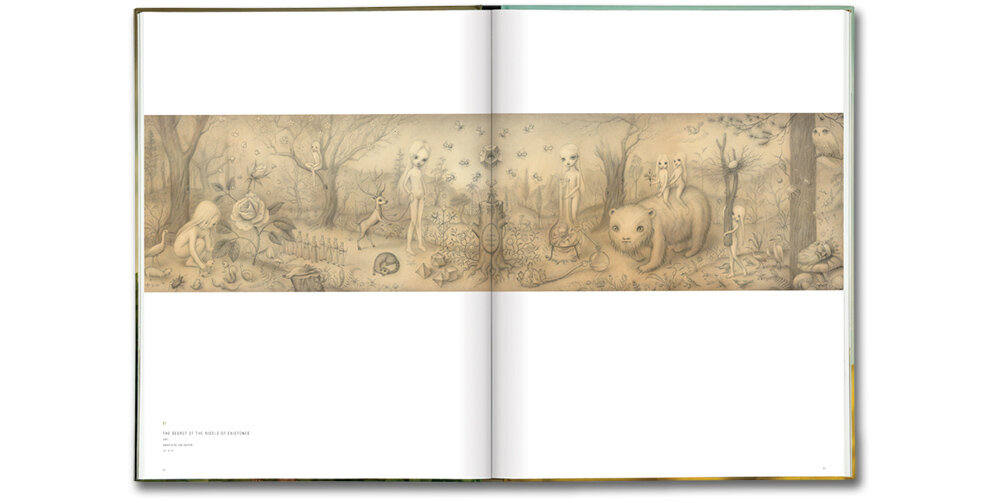

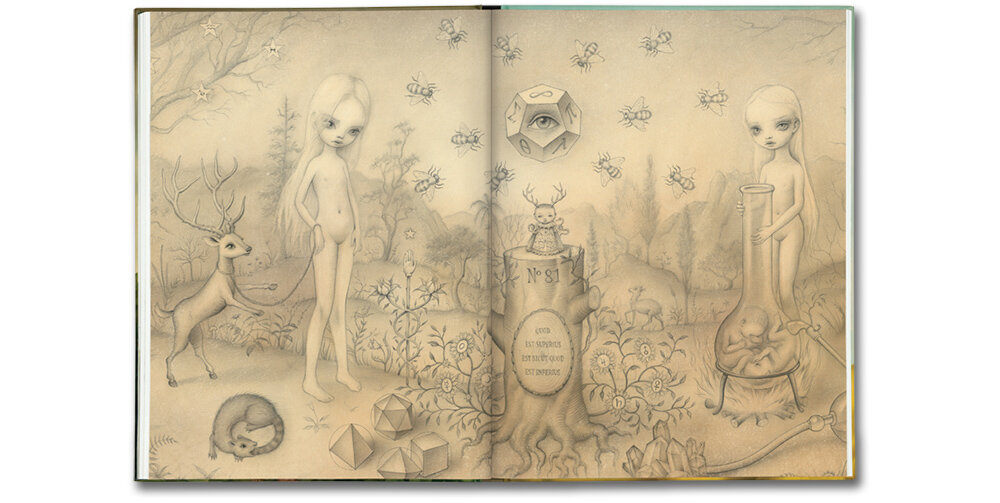

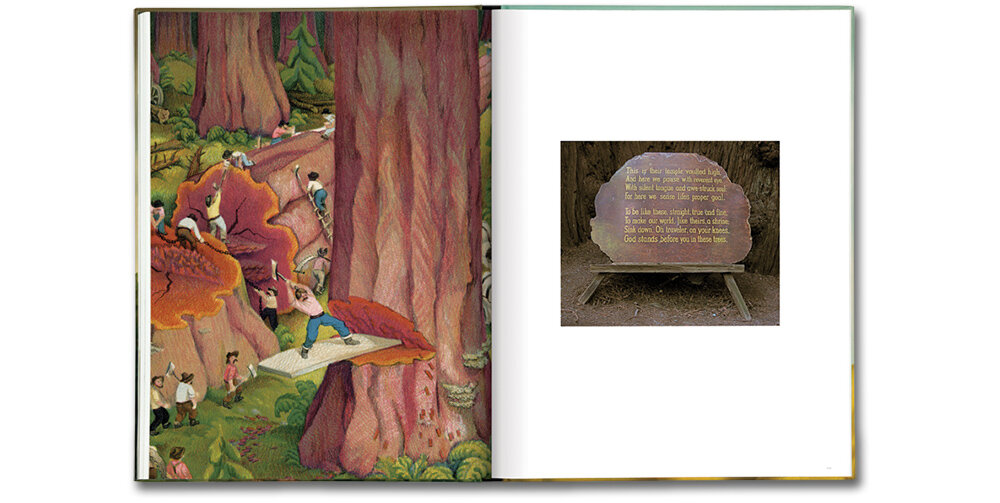

Having functionally banished the likes of Apollo (the only comparable figure is a devil driving a logging truck, but he keeps to the road), Ryden leaves his nymphs free to roam in a state of prelapsarian wonder. As surrogates for the viewer, they present the possibility of a kinder, gentler relationship to nature, one driven by compassion and curiosity rather than covetousness and aggression. At peace with the bears, squirrels and other animals that populate this world, they approach the trees with reverence, as keepers of secrets and sacred knowledge, their wisdom frequently connoted by the presence of a single, centralized eye-an eye that registers the devastation man has wrought with weary resignation. In an especially lovely painting called The Apology, a girl in a yellow dress sits before an upturned stump, her hands raised in a gesture of graceful conciliation. An eye at the center of the stump receives the offering with dignity. The painting's hand-carved frame, meanwhile, radiates with delicate tendrils that echo the roots of the stump, expanding its presence magically outward, into the space of the gallery itself. Bernini's Apollo and Daphne is a violent swirl of a sculpture, characterized by a tumbling forward propulsion that seems liable to lift the marble into the air at any moment; The Apology, by contrast, is the very image of equilibrium: humanity and nature in balance.

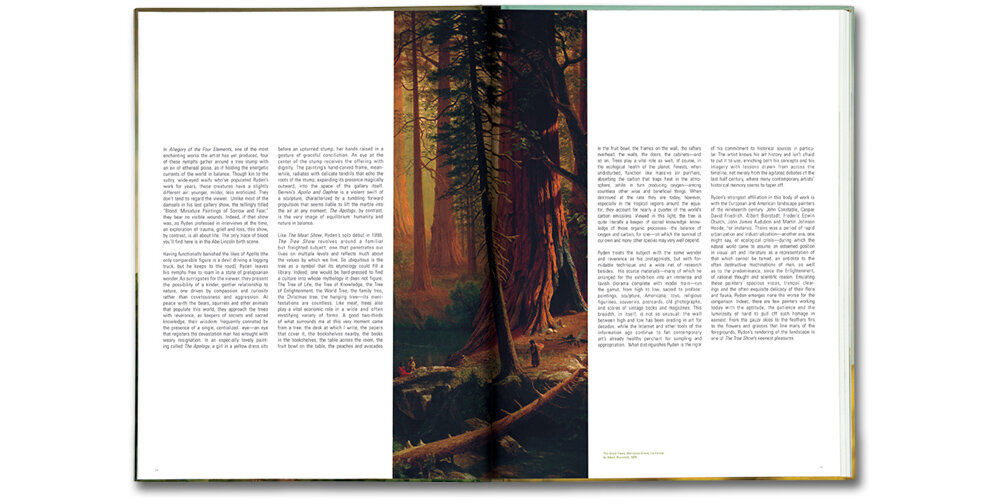

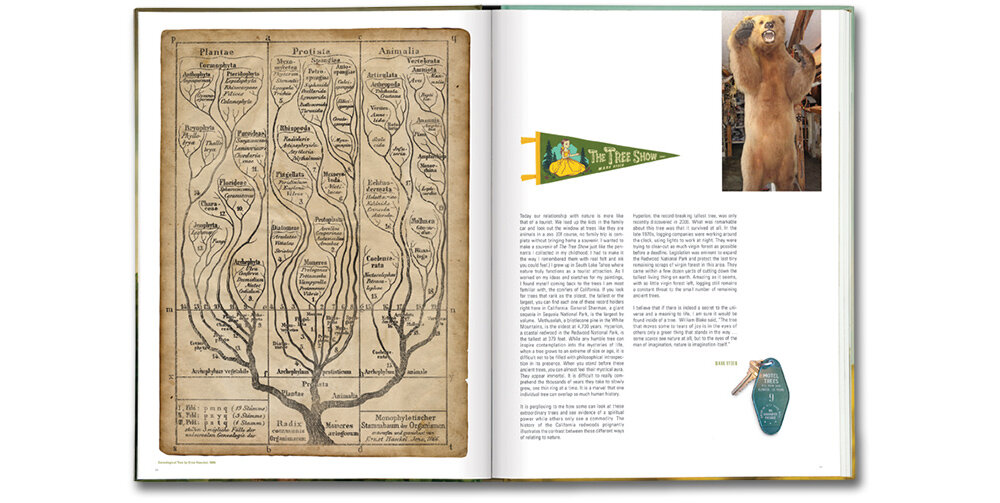

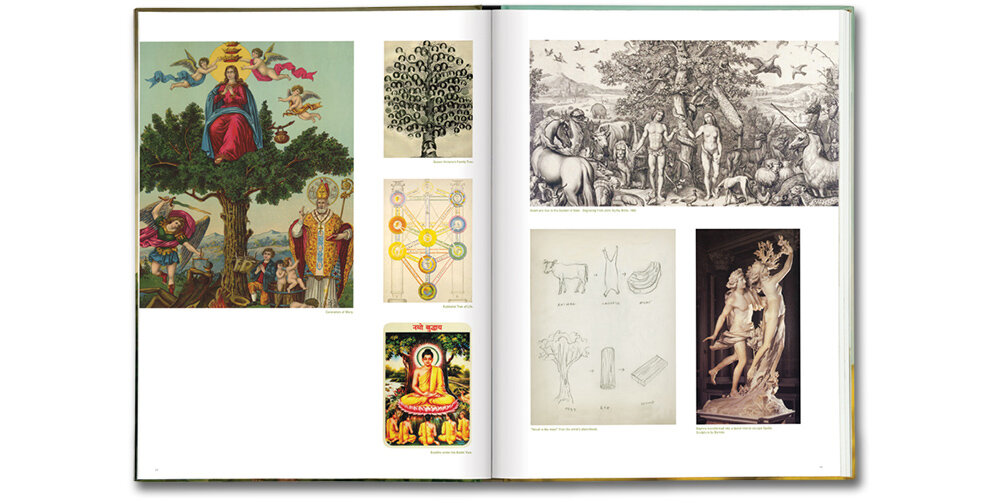

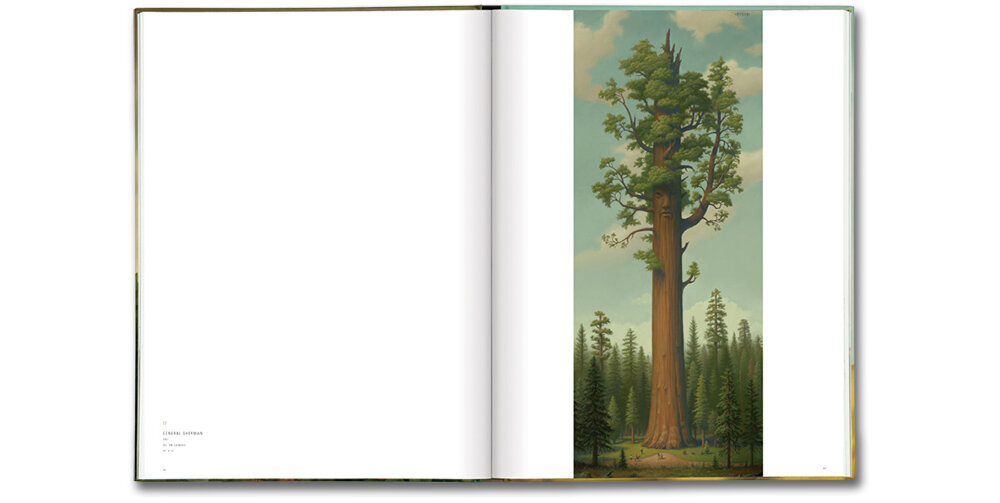

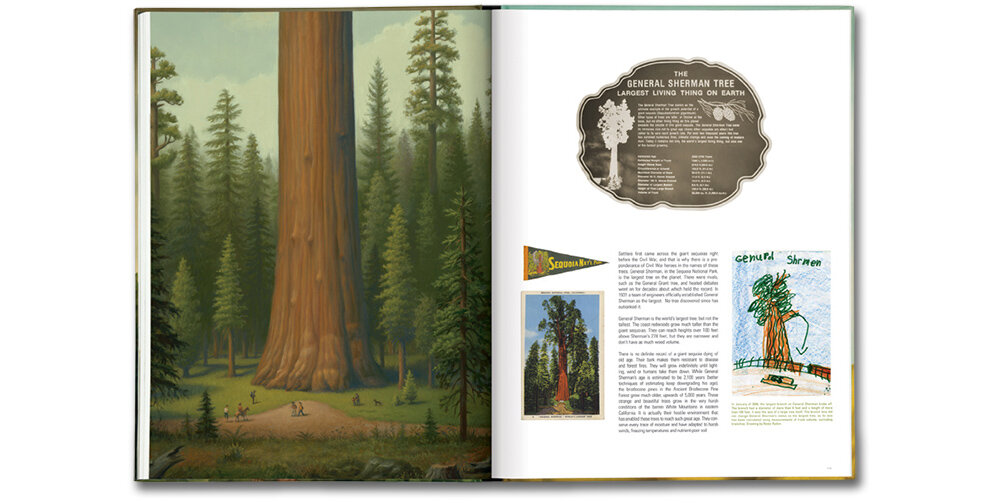

Like The Meat Show, Ryden's solo debut in 1998, The Tree Show revolves around a familiar but freighted subject, one that penetrates our lives on multiple levels and reflects much about the values by which we live. So ubiquitous is the tree as a symbol that its etymology could fill a library. Indeed, one would be hard-pressed to find a culture into whose mythology it does not figure. The Tree of Life, the Tree of Knowledge, the Tree of Enlightenment, the World Tree, the family tree, the Christmas tree, the hanging tree-its manifestations are countless. Like meat, trees also playa vital economic role in a wide and often mystifying variety of forms. A good two-thirds of what surrounds me at this very moment came from a tree: the desk at which I write, the papers that cover it, the bookshelves nearby, the books in the bookshelves, the table across the room, the fruit bowl on the table, the peaches and avocados in the fruit bowl, the frames on the wall, the rafters overhead, the walls, the doors, the cabinets-and so on. Trees play a vital role as well, of course, in the ecological health of the planet. Forests, when undisturbed, function like massive air purifiers, absorbing the carbon that traps heat in the atmosphere, while in turn producing oxygen-among countless other wise and beneficial things. When destroyed at the rate they are today, however, especially in the tropical regions around the equator, they account for nearly a quarter of the world's carbon emissions. Viewed in this light, the tree is quite literally a keeper of sacred knowledge: know-ledge of those organic processes-the balance of oxygen and carbon, for one-on which the survival of our own and many other species may very well depend.

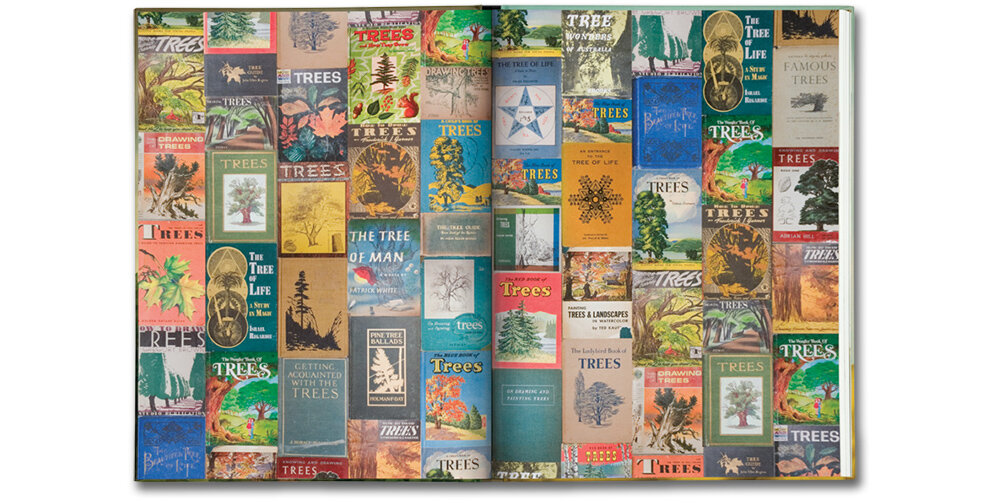

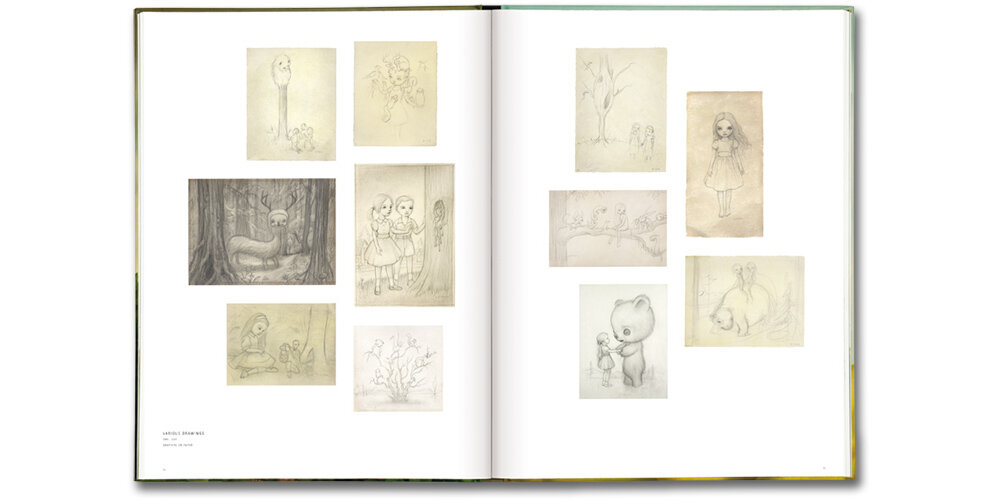

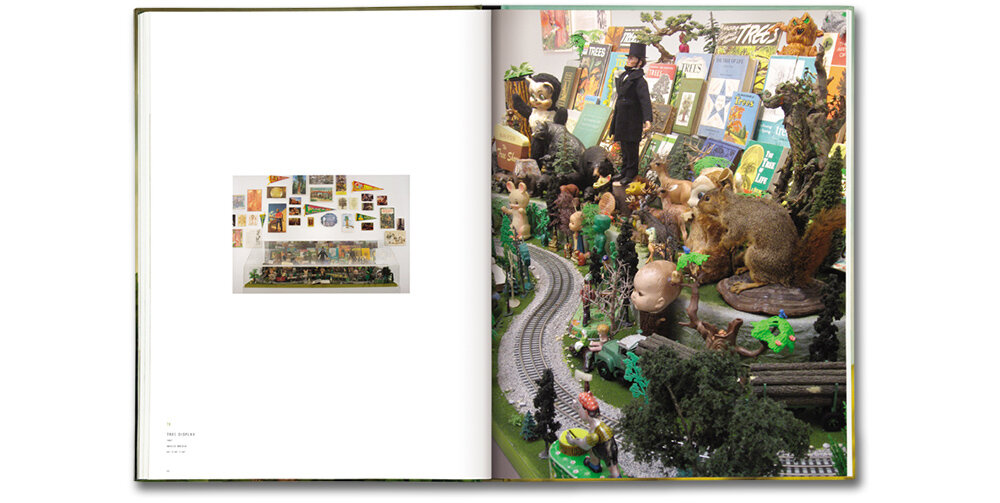

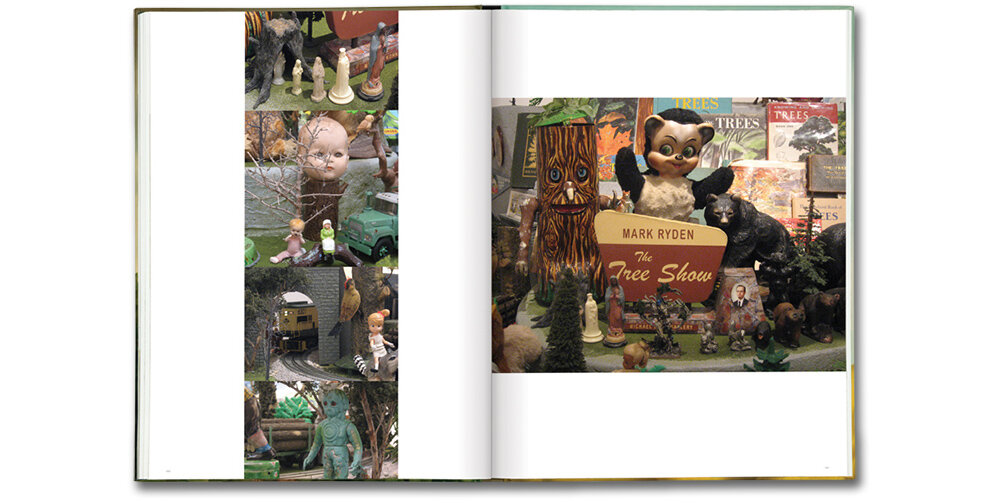

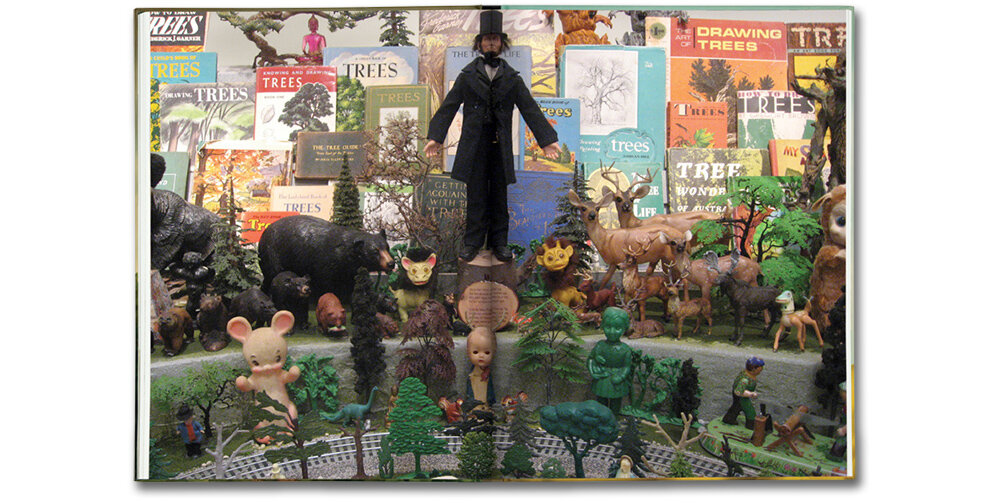

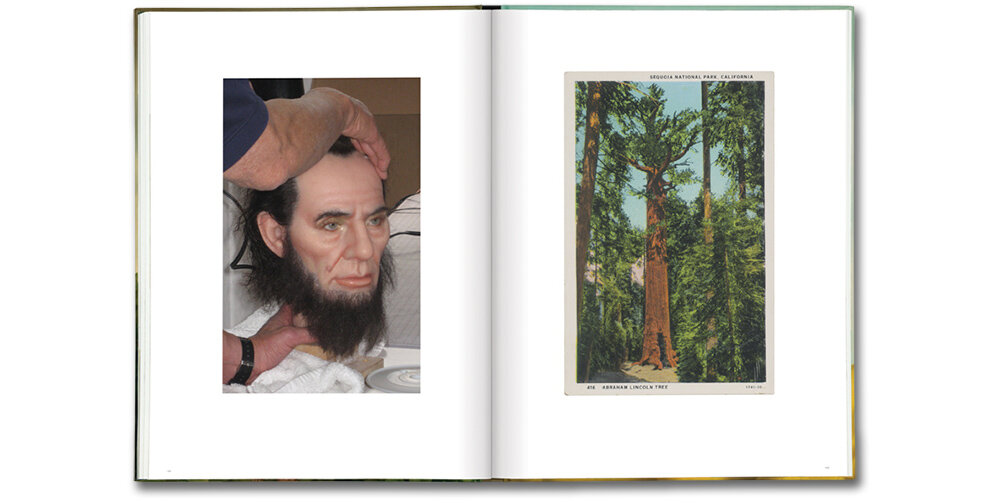

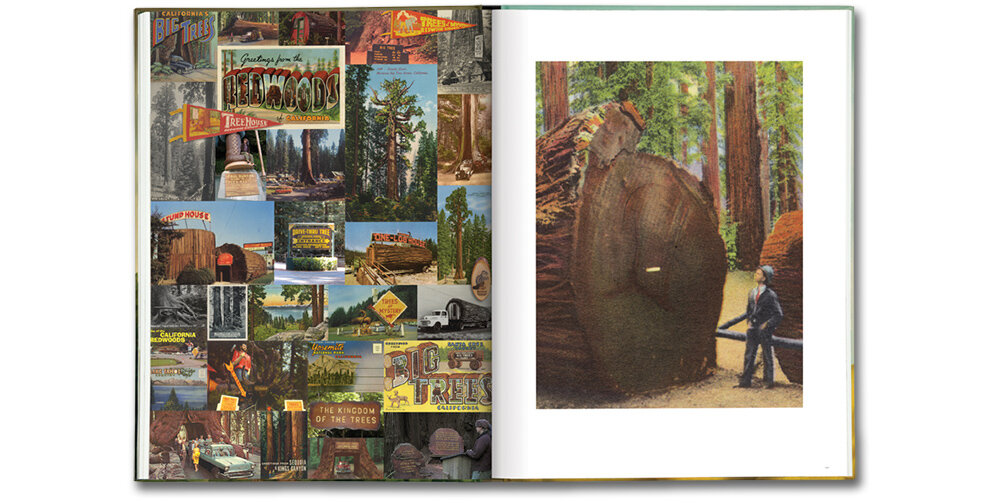

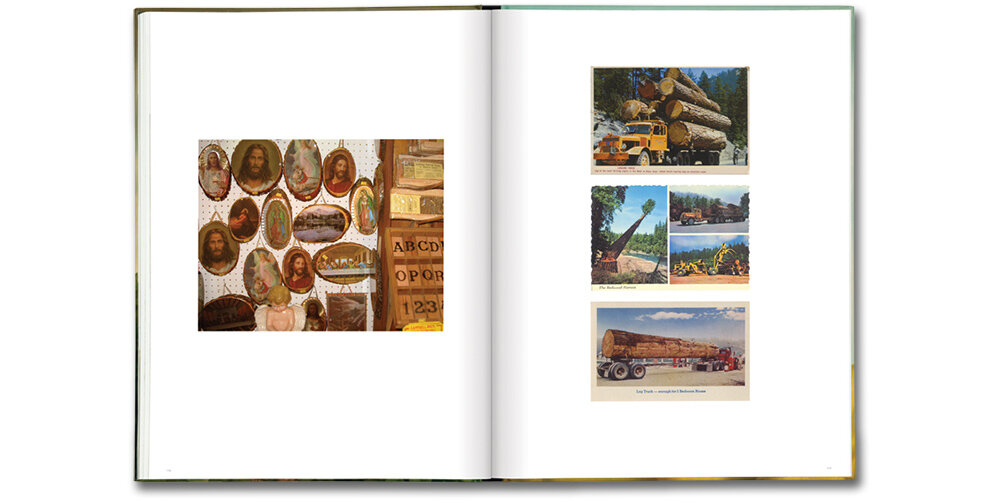

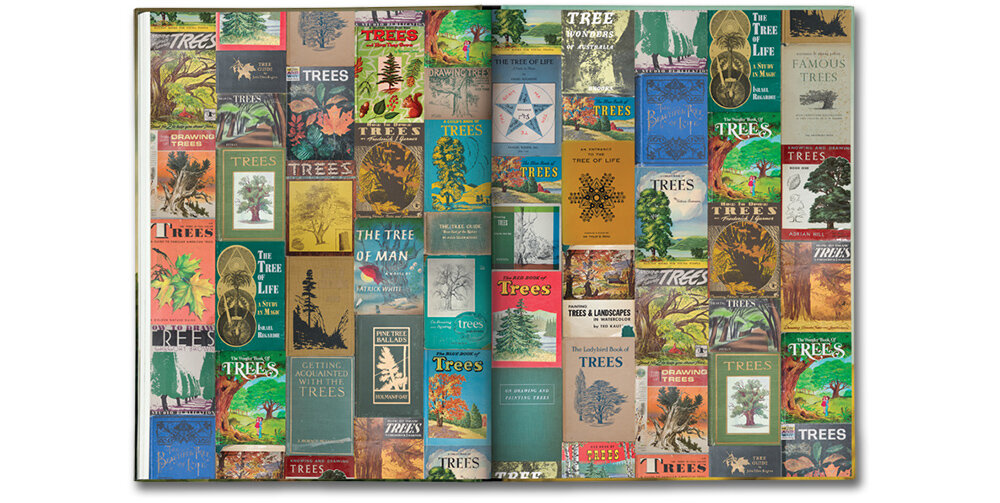

Ryden treats the subject with the same wonder and reverence as his protagonists, but with formidable technique and a wide net of research besides. His source materials-many of which he arranged for the exhibition into an immense and lavish diorama complete with model train-run the gamut, from high to low, sacred to profane: paintings, sculpture, Americana, toys, religious figurines, souvenirs, postcards, old photographs, and scores of vintage books and magazines. This breadth, in itself, is not so unusual: the wall between high and low has been eroding in art for decades, while the Internet and other tools of the information age continue to fan contemporary art's already healthy penchant for sampling and appropriation. What distinguishes Ryden is the rigor of his commitment to historical sources in particular. The artist knows his art history and isn't afraid to put it to use, enriching both his concepts and his imagery with lessons drawn from across the timeline, not merely from the agitated debates of the last half century, where many contemporary artists' historical memory seems to taper off.

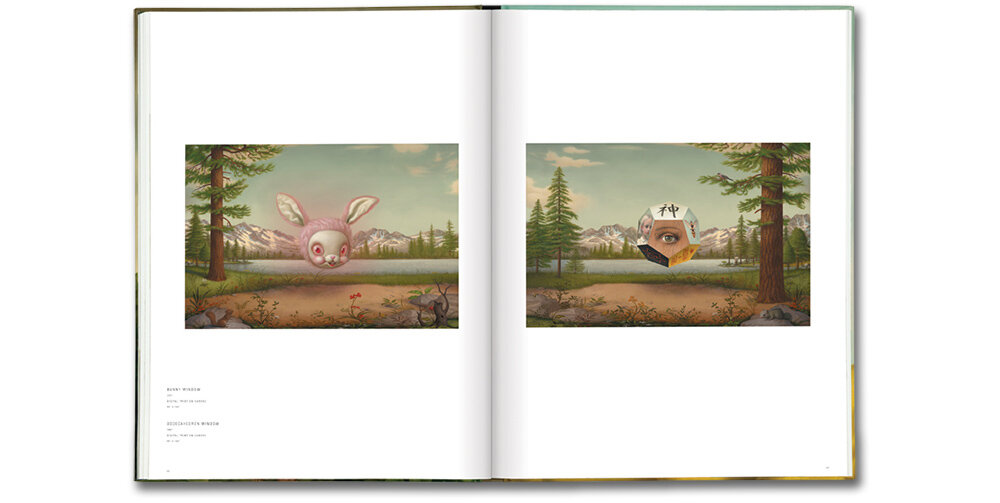

Ryden's strongest affiliation in this body of work is with the European and American landscape painters of the nineteenth century: John Constable, Caspar David Friedrich, Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, John James Audubon and Martin Johnson Heade, for instance. Theirs was a period of rapid urbanization and industrialization-another era, one might say, of ecological crisis-during which the natural world came to assume an esteemed position in visual art and literature as a representation of that which cannot be tamed, an antidote to the often destructive machinations of man, as well as to the predominance, since the Enlightenment, of rational thought and scientific reason. Emulating these painters' spacious vistas, tranquil clearings and the often exquisite delicacy of their flora and fauna, Ryden emerges none the worse for the comparison. Indeed, there are few painters working today with the aptitude, the patience and the luminosity of hand to pull off such homage in earnest. From the gauzy skies to the feathery firs to the flowers and grasses that line many of the foregrounds, Ryden's rendering of the landscape is one of The Tree Show's keenest pleasures.

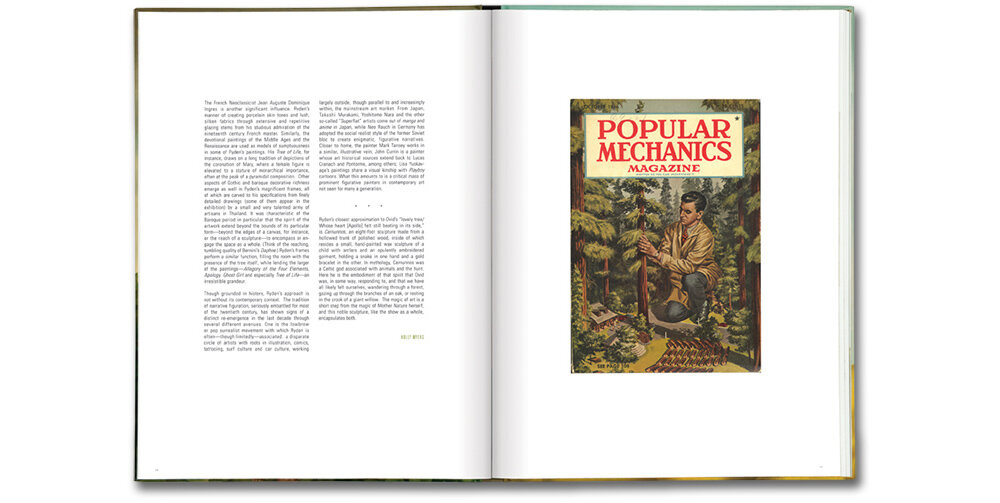

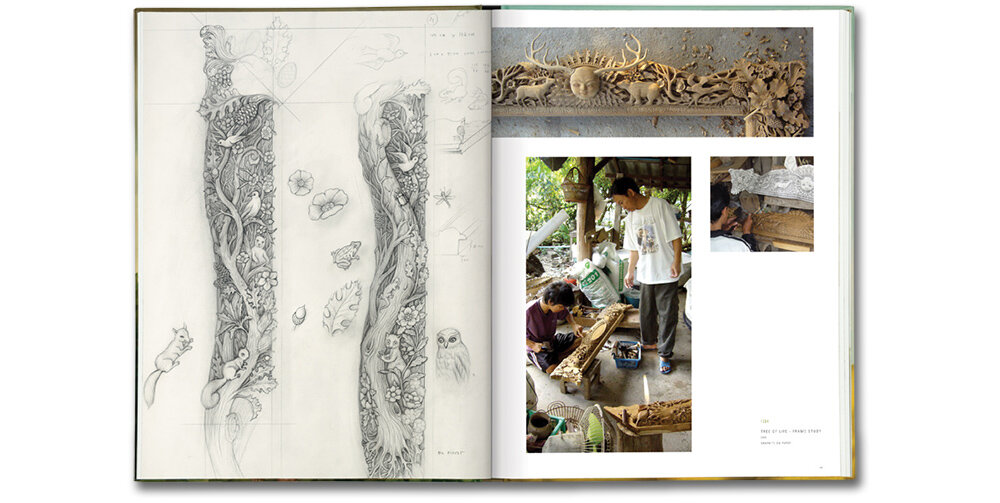

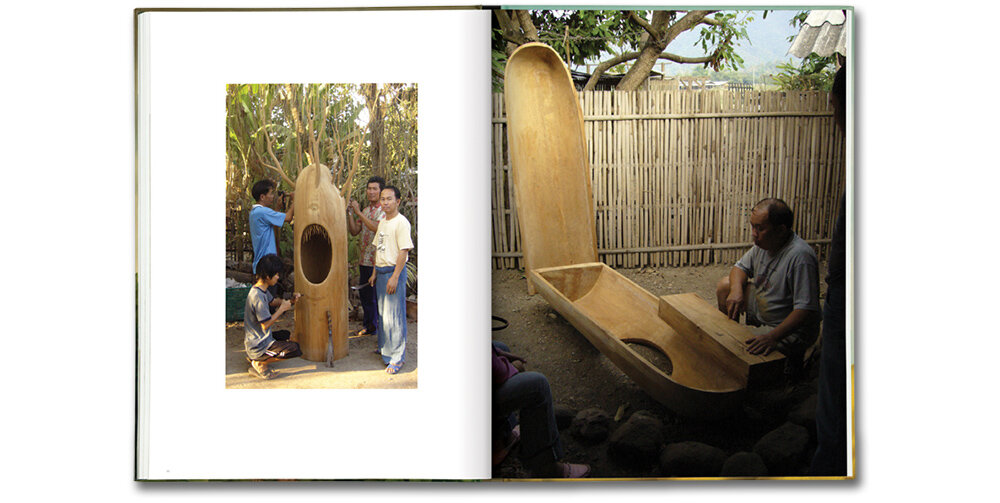

The French Neoclassicist Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres is another significant influence. Ryden's manner of creating porcelain skin tones and lush, silken fabrics through extensive and repetitive glazing stems from his studious admiration of the nineteenth century French master. Similarly, the devotional paintings of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance are used as models of sumptuousness in some of Ryden's paintings. His Tree of Life, for instance, draws on a long tradition of depictions of the coronation of Mary, where a female figure is elevated to a stature of monarchical importance, often at the peak of a pyramidal composition. Other aspects of Gothic and baroque decorative richness emerge as well in Ryden's magnificent frames, all of which are carved to his specifications from finely detailed drawings (some of them appear in the exhibition) by a small and very talented army of artisans in Thailand. It was characteristic of the Baroque period in particular that the spirit of the artwork extend beyond the bounds of its particular form-beyond the edges of a canvas, for instance, or the reach of a sculpture-to encompass or engage the space as a whole. (Think of the reaching, tumbling quality of Bernini's Daphne.) Ryden's frames perform a similar function, filling the room with the presence of the tree itself, while lending the larger of the paintings-Allegory of the Four Elements, Apology, Ghost Girl and especially Tree of Life-an irresistible grandeur.

Though grounded in history, Ryden's approach is not without its contemporary context. The tradition of narrative figuration, seriously embattled for most of the twentieth century, has shown signs of a distinct re-emergence in the last decade through several different avenues. One is the lowbrow or pop surrealist movement with which Ryden is often-though limitedly-associated: a disparate circle of artists with roots in illustration, comics, tattooing, surf culture and car culture, working largely outside, though parallel to and increasingly within, the mainstream art market. From Japan, Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara and the other so-called "Superflat" artists come out of manga and anime in Japan, while Neo Rauch in Germany has adopted the social realist style of the former Soviet bloc to create enigmatic, figurative narratives. Closer to home, the painter Mark Tansey works in a similar, illustrative vein; John Currin is a painter whose art historical sources extend back to Lucas Cranach and Pontormo, among others; Lisa Yuskavage's paintings share a visual kinship with Playboy cartoons. What this amounts to is a critical mass of prominent figurative painters in contemporary art not seen for many a generation.

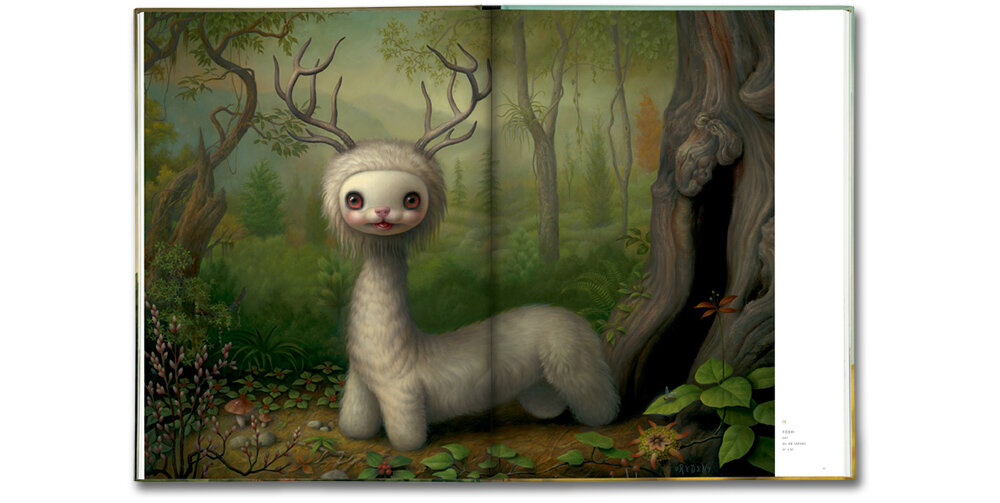

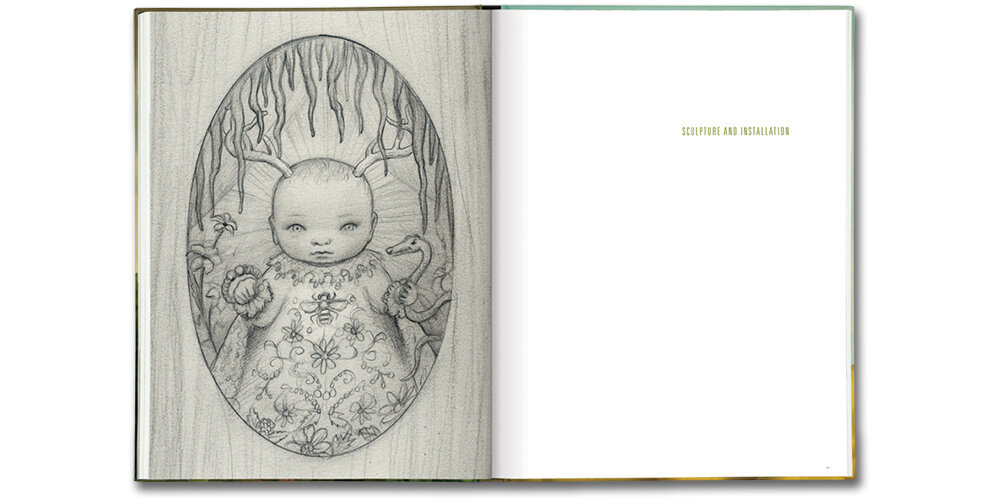

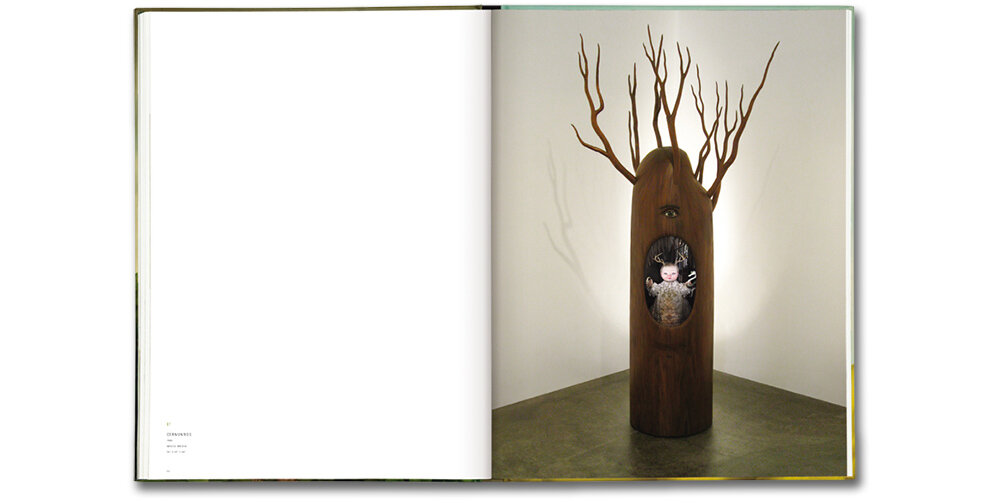

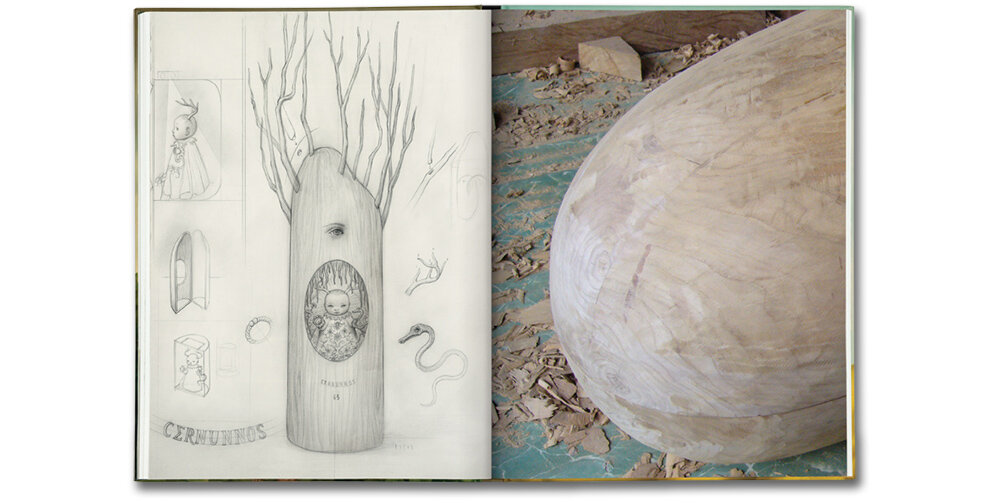

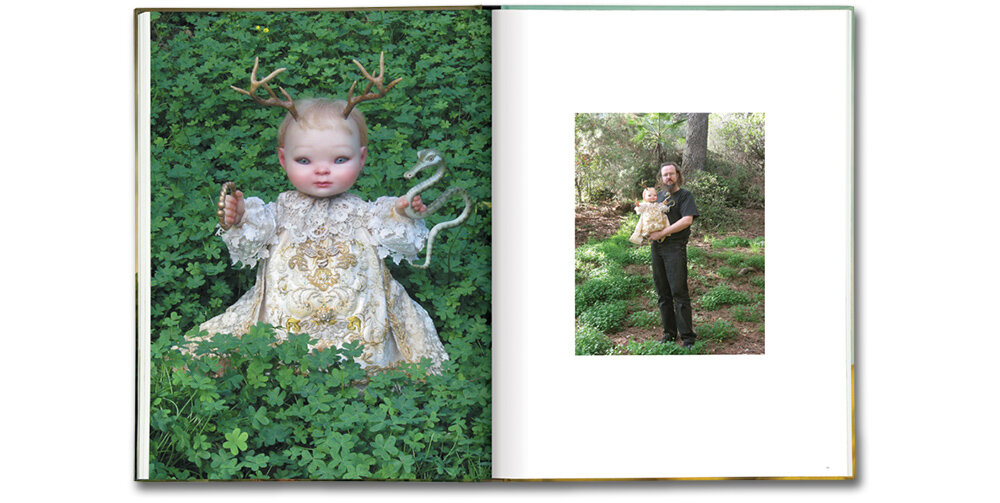

Ryden's closest approximation to Ovid's "lovely tree/ Whose heart [Apollo] felt still beating in its side," is Cernunnos, an eight-foot sculpture made from a hollowed trunk of polished wood, inside of which resides a small, hand-painted wax sculpture of a child with antlers and an opulently embroidered garment, holding a snake in one hand and a gold bracelet in the other. In mythology, Cernunnos was a Celtic god associated with animals and the hunt. Here he is the embodiment of that spirit that Ovid was, in some way, responding to, and that we have all likely felt ourselves, wandering through a forest, gazing up through the branches of an oak, or resting in the crook of a giant willow. The magic of art is a short step from the magic of Mother Nature herself, and this noble sculpture, like the show as a whole, encapsulates both.