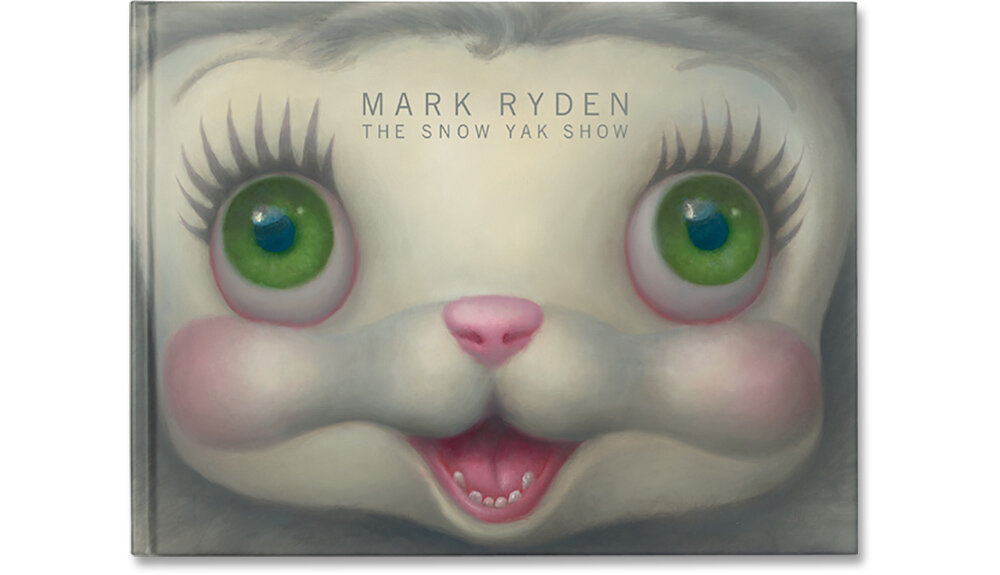

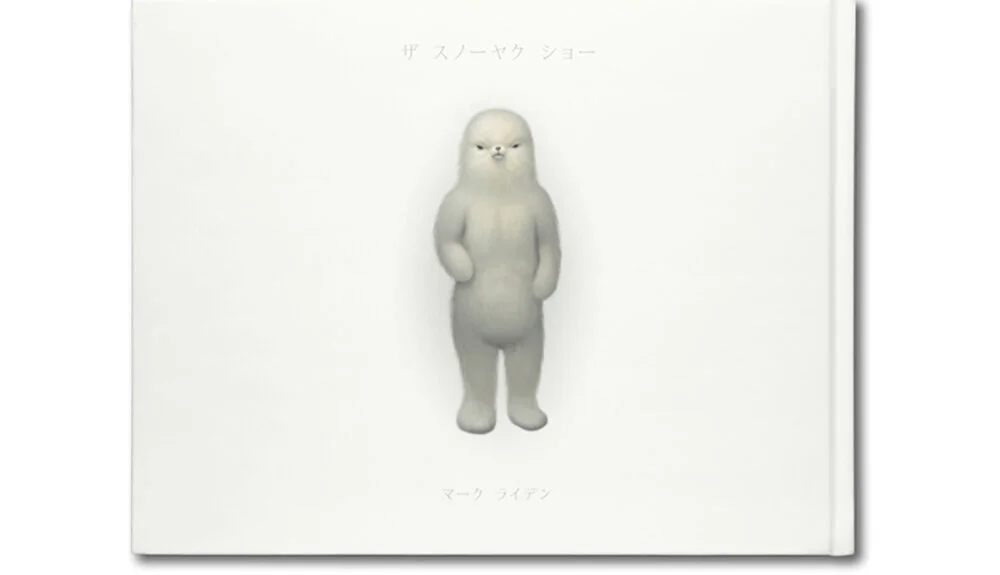

The Snow Yak Show Exhibition Book

Publisher: Last Gasp

"Mark Ryden and the Snow Yak" - Essay by Kirsten Anderson

2010

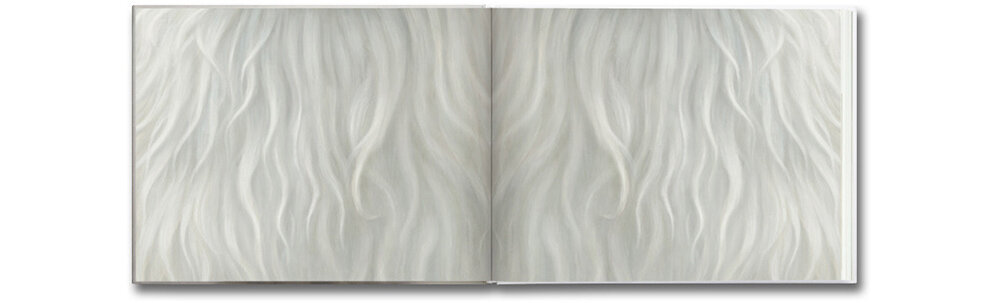

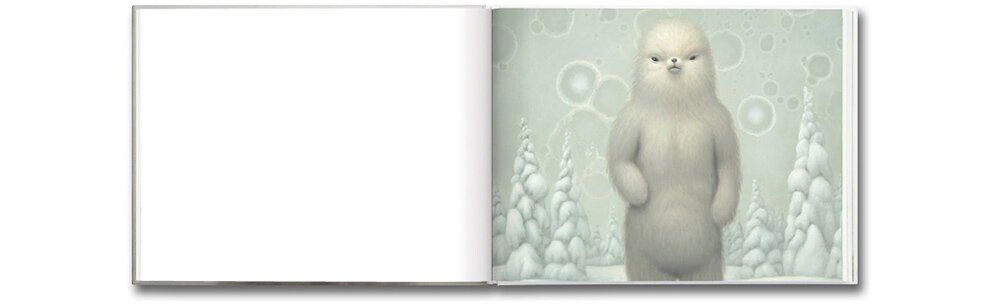

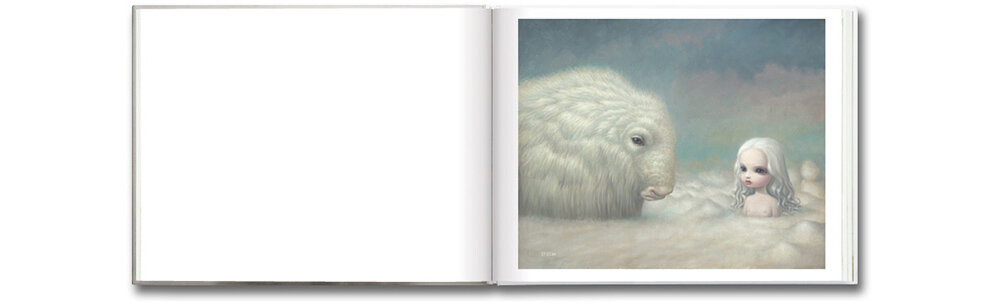

If Ryden's previous exhibition "Blood" seemed like an inward scream, "The Tree Show" an environmental exaltation, then "The Snow Yak Show" reveals itself like a meditative exhalation. This latest body of work features an array of new scenes set in a mystical snow encrusted land populated by ghostly pale moon children and highly uncanny yet softly benevolent creatures. In these seven paintings (accompanied by a handful of drawings and sketches), the tone is less carnivalesque and more serene than previous works. The color palette is based on whites, though hardly bleached out, richly tinged with tones of grays, blues and pinks. Generally, the compositions are more iconic, and suggestive of solitude, peacefulness and introspection. Backgrounds, normally painted in representational detail, are articulated fields of monochrome. Some of the works include previously unseen abstract painting effects (like the melted snowflake background in Abominable).

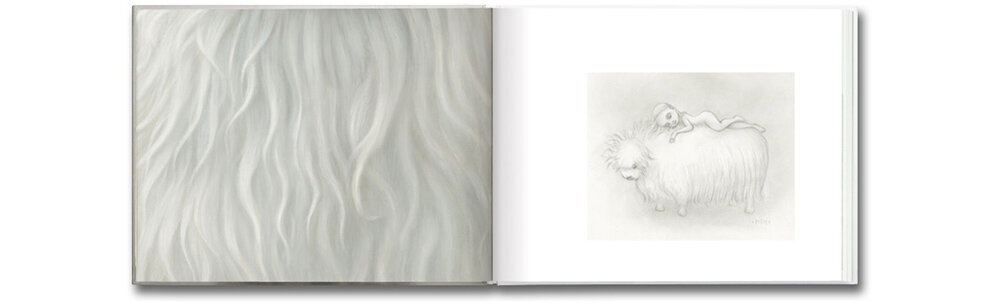

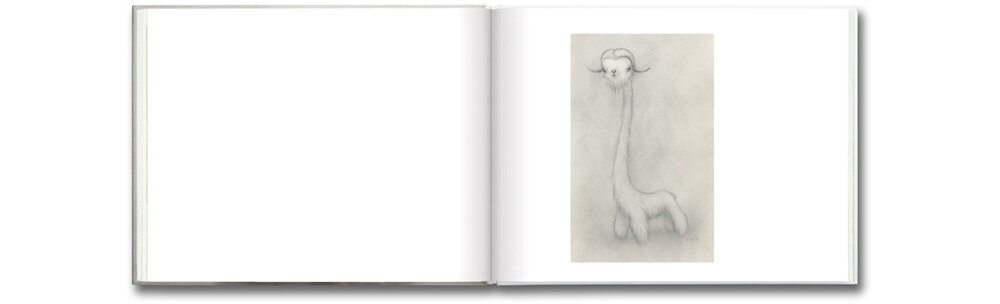

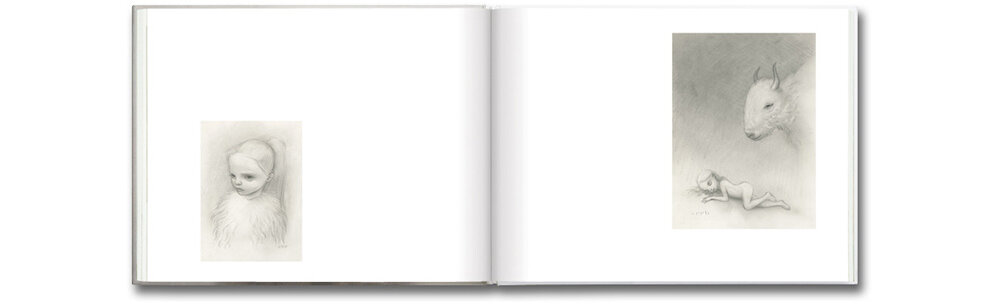

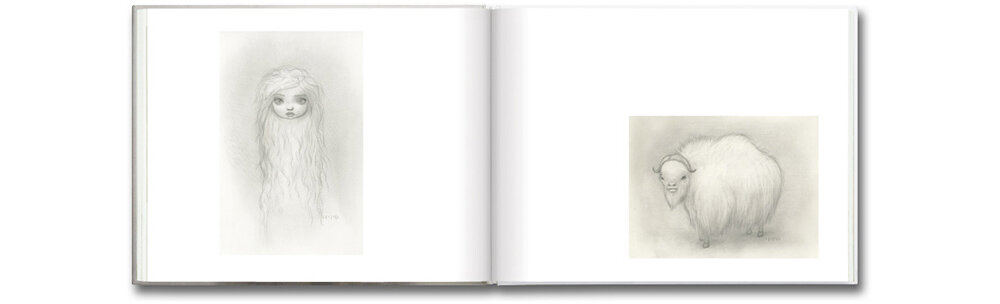

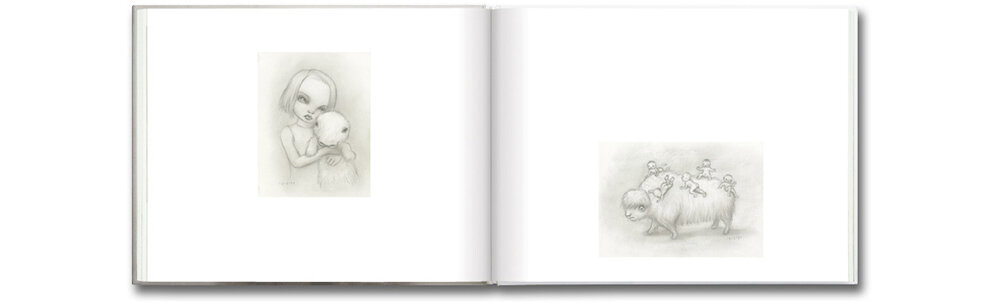

The drawings are of girls, and of the amorphous snow yaks that are rendered as unlikely creatures not found in the real world - more of a spiritual companion loosely resembling a real animal. These drawings were exhibited in a separate room and indeed seem to contain a whole expression and theme unto themselves, more connected to each other than the paintings. In the drawings, girls lovingly coddle baby yaks and adult yaks take maternal turns watching over human babies, all with no real hint of the morbid humor Ryden's work can often generate. An un-ironic, sincere gentleness pervades each scene, which in these days is almost as shocking as violence.

The theme of snow infuses all of the paintings. When asked if the inspiration had anything to do with the show's Japanese location (where many folktales and myths occur in the snow) Ryden says simply that he was already inspired to go the minimalist and white route but maybe thought the link was a welcome association for people anyhow. This series, which took about a year to complete, also maintains a sparseness in its framing. Rather than the over-the-top, ornate frames Ryden usually has custom carved as an extension of each painting, this show was framed in simple, unobtrusive white frames, emphasizing their sparsity but also allowing the viewer to focus more truly on the painting.

Without a doubt, Mark Ryden is one of the biggest names in contemporary art right now. His works have attracted hordes of admirers, from celebrities to museum board members to Goth high school kids. But that is not the really interesting thing about the artist. For him, the mystery is more important than the message. In fact, mystery often is the message. When questioned about the symbolism and meaning in his paintings, which are riddled with images taken from alchemical texts, foreign languages and numerology, Ryden remains willfully obscure. He prefers the narrative to remain cryptic, and he wants to evoke a sense of wonder and curiosity within the viewer rather than producing work that can be quickly deciphered. And indeed, while his technical craftsmanship is beyond question, what causes people to react so viscerally to Ryden's work is his idiosyncratic imagery and the way he uses it. Through his looking glass lens the artist is able to imbue modern day pop artifacts and sci-fi marvels with the same sense of wonderment any 19th century fireside fairytale possesses. Some critics dismiss Ryden's work as mere pop culture kitsch just painted all fancy, a visual snake oil act. However, beyond the use of modern day cultural flotsam and jetsam (which you either get or you don't, and/or like or don't) a complex system of archetypal and mythical imagery, as well as references to the arcane, emerges.

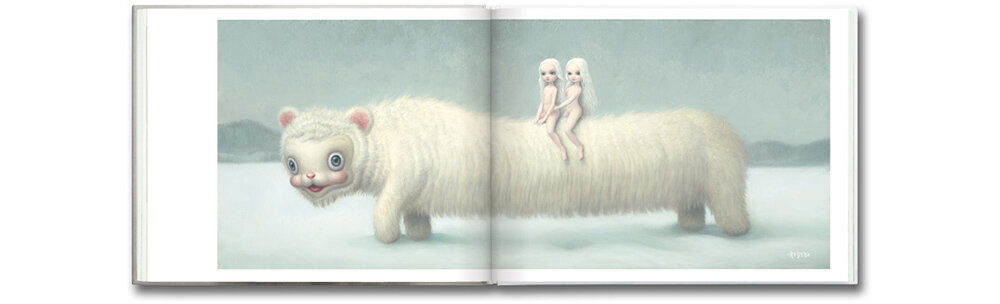

In fact, to "understand" a Ryden painting you'd do better to read Guy Murchie's The Seven Mysteries of Life, a science textbook, or a book by Joseph Campbell before any tome on the history of art theory. Ryden himself is very Zen-like in his acceptance of other people's interpretations of his work. He says he finds it gratifying that people can see different things in the paintings. He never seems to confirm or deny any particular interpretation because what matters most is the feeling his work evokes rather than an intellectual understanding. Incidentally, Ryden himself says the show was inspired by a dream: I had an intense dream of the long creature I painted in Long Yak. In the dream, I was in the belly of one yak, while looking out an opening at the long yak. This dream was quite vivid. Dreams of ice can come from deep in the psyche. Clean white snow seems to come from the realm of the spirit.

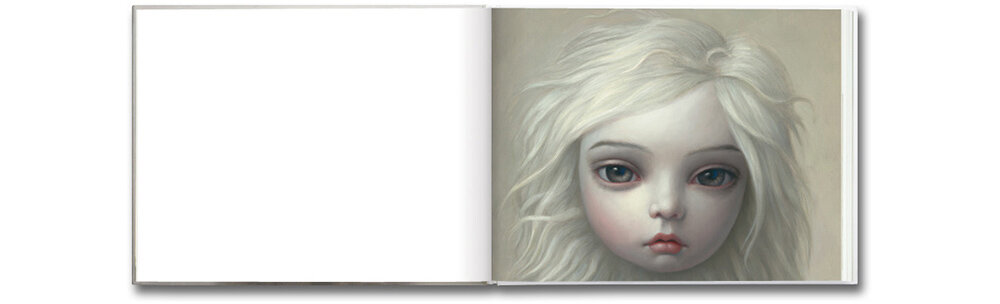

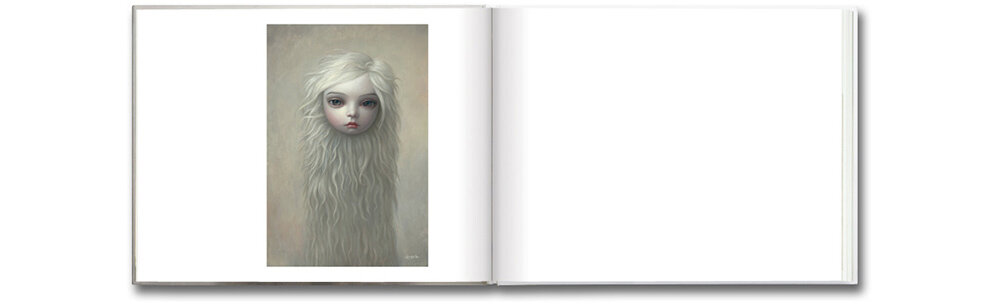

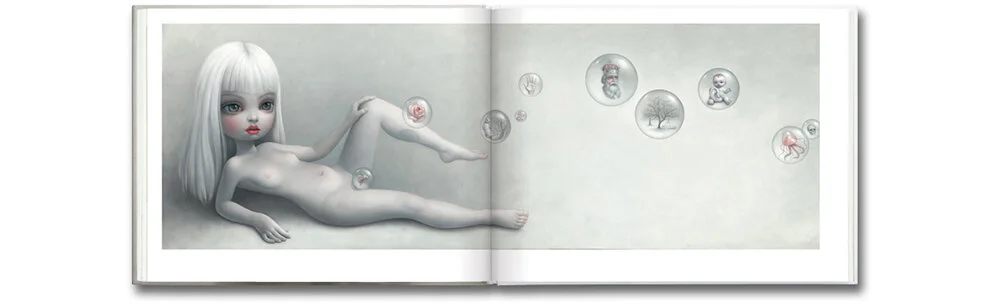

In Long Yak, two twin-like girls ride the back of a strange toy-faced beast through a snow-covered land. Twins connote a range of symbolic meanings, while their pose on the back of this creature is reminiscent of images of Hindu deities (such as Durga, who is occasionally considered a virgin/pure goddess figure). Those deities are depicted as riding on animals, such as tigers or lions, denoting a conquering of "animalistic" desires or the mastery of the ego and willpower. Clearly, Ryden's whole raison d'etre of painting is about mystery and transcendence. He speaks freely about the Muse (in his case he flippantly refers to it as a magic monkey that squats on his shoulder in the wee hours). In "The Snow Yak Show," the muse takes the shape of a young white haired girl, tellingly named "Sophia." Sophia is also the name of a universal cosmic principle, a goddess of wisdom or God's consort depending on which version you like. She appears as a "pure virgin" according to some, whose downfall led to the manifestation of the physical world.

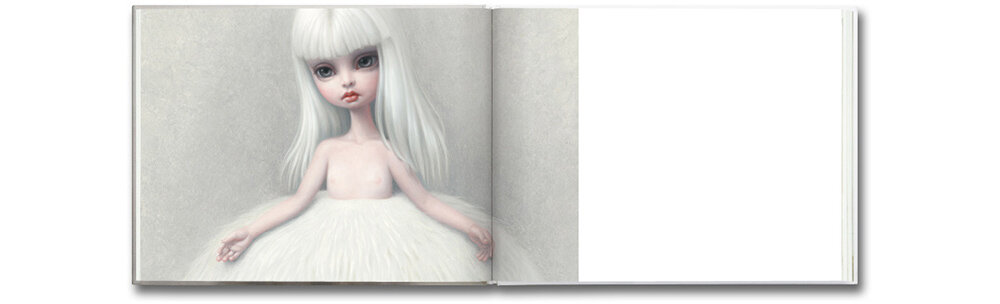

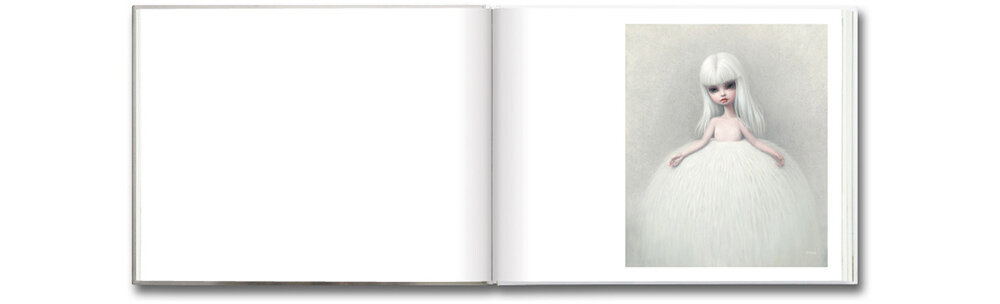

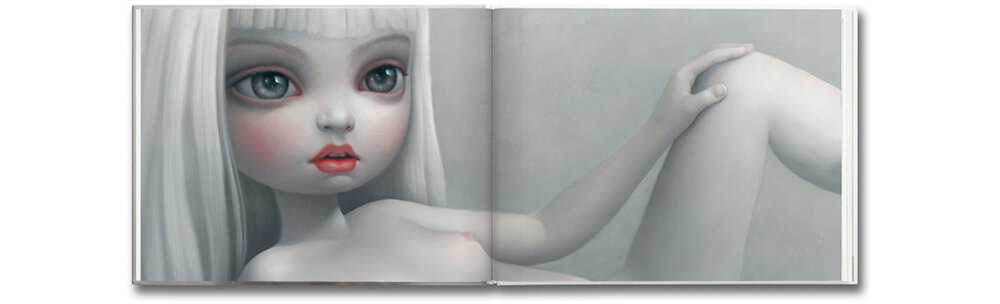

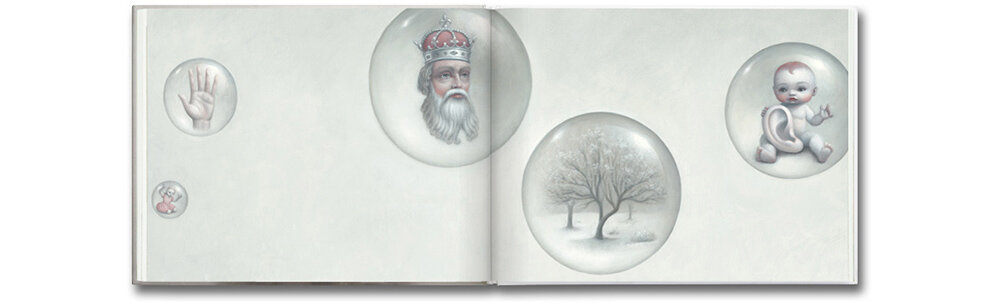

This sheds an interesting light on arguably Ryden's most provocative painting to date, Sophia's Bubbles. A pale young woman reclines across an abstract, highly nuanced background. This figure is an elegant and languid young female who projects the qualities of both innocence and godliness. Sophia emanates bubbles from her loins (albeit in the manner of a Thai pingpong ball show), each of which contains a symbol representing a planet in our solar system. Ultimately, this theme harkens back to perhaps the oldest of human myths, the creation of the Universe. This idea of "purity" and serenity is also evident in the sublimely beautiful Girl in a Fur Skirt. As in Sophia's Bubbles, it features an archetypal female figure in a classic Virgin Mary pose, with an open armed, passive and compassionate stance, a wistful countenance and clad in a white fur skirt which conceals her stomach but reveals her breasts. It is curious to wonder how the fur was acquired: Even a figure of high purity demands a certain sacrifice-offered willingly, or not. Ryden's consistent depiction of children, predominantly girls, as virginal figures continues to act as a foil for the surrealist circus that swirls around them.

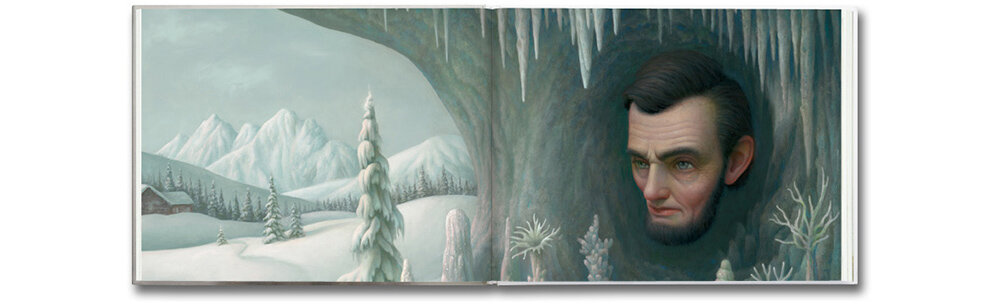

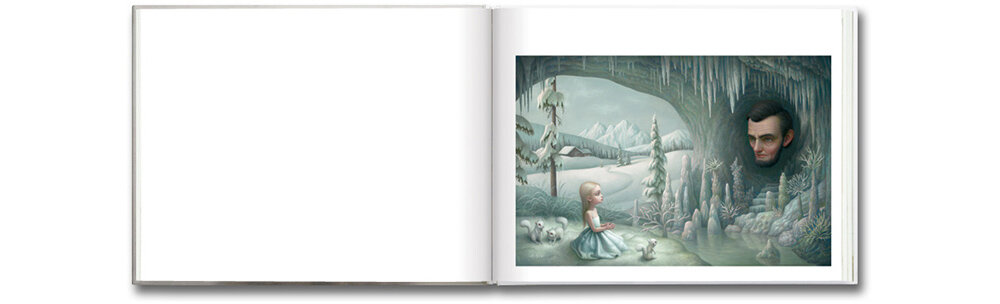

In "The Tree Show," the girls are often wood nymphs, possessors or discoverers of secrets held within the natural world. In "The Snow Yak Show," they seem to be more like representations of a holier ideal, a personification of purity. However, pure does not necessarily guarantee complete innocence. These blonde, waiflike figures seem to carry a heavier burden and embody a more considered thoughtfulness than previous "characters" in Ryden's work. They succumb to the physicality that, at the same time, ties them to the world and to the role that elevates them above it. Grotto of the Old Mass recalls a classic "Our Lady of Lourdes" scene that has been immortalized in countless pieces of plastic, kitschy souvenirs one finds in religious gift shops throughout the world. The scene commemorates the "true" story of a young girl in Southern France who claimed Mary appeared to her in a cave, and warned her of worldly hardships to come. In Ryden's version, the apparition of Abraham Lincoln replaces that of the Virgin Mary. The 16th American president (a favorite subject of the artist who appears in many of his works) has been mythologized into a historical figure of compassionate wisdom within American culture, someone who is reverentially invoked when talking about the highest of ideals and yet whose image is also used to sell cars and "tchotckes" on national holidays. Disembodied heads recur in art from early Celtic works to the radiant pastels of Odilon Redon and they can convey an array of meanings.

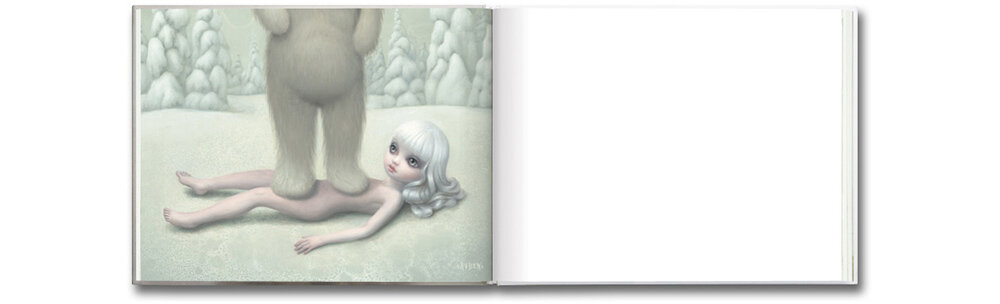

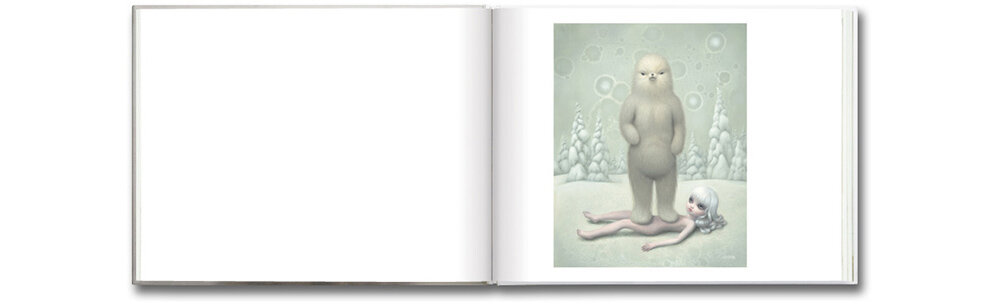

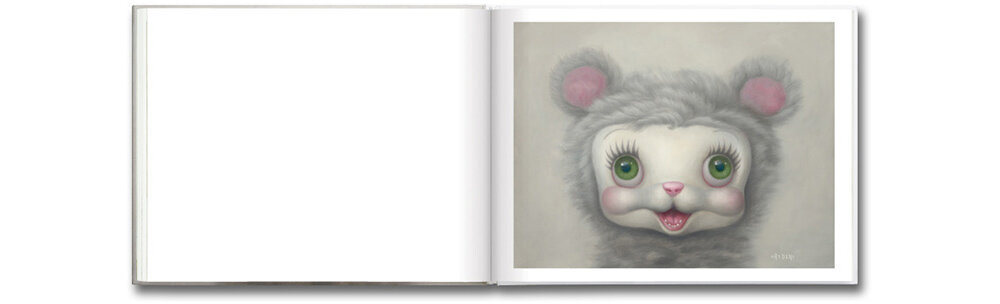

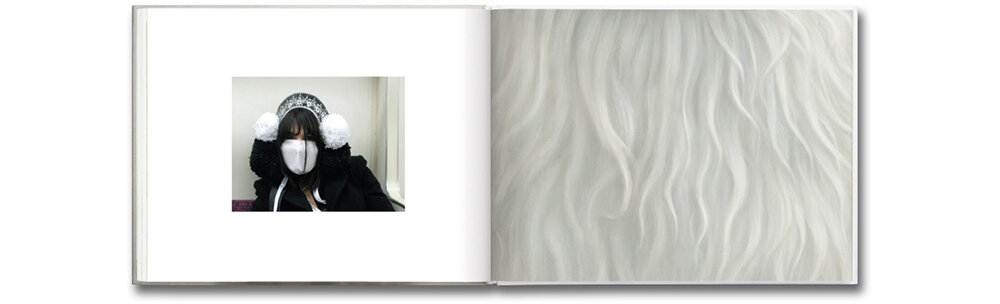

In Fur Girl the enigmatic subject appears to float tranquilly within the void of the nuanced background, sporting a luxurious fall of yak-like hair. This hirsute honey has a halo of hair that frames her doll-like face, her crystal clear eyes and her direct gaze. This figure is more like an oracle than anything else, a figure that crosses between worlds to relay information, and her wooly tresses of hair suggests a feral wildness that has been somewhat tamed. In fact, one of the few paintings in "The Snow Yak Show" that exhibits any sort of palpable tension (despite pervasive unnerving imagery) is Abominable. Here, a yeti-like creature stands and squints atop another bemused Sophia-like character. Do the wild, unpredictable and uncontrollable aspects of Nature triumph over man's quest for enlightenment? Or is it the other way around?

Indeed, with all the works in "The Snow Yak Show," and in all of Ryden's paintings, one could spend hours unraveling the symbolism and references. The examples provided are merely speculations rather than certain, sanctified insight into Ryden's arcane treasure trove of historical and cultural imagery. The important thing is that beyond Ryden's formidable painting skill and singular vision is his achievement in the role of a dream merchant. He is an artist/magician who is profoundly able to express questions about the unknowable in pictorial form, and who appreciates the mysteries of science and the universal without judging it (and while having a great sense of humor about it at the same time) and unselfconsciously hoping it will ignite the spark of wonder within others. This essay first appeared in Hi-Fructose Magazine, vol. 11 People have the idea that an image must 'stand for' something else, that the "real" meaning needs to be described with language. Instead it is the image itself that is the meaning.