Venice Magazine

Welcome to Mark Ryden's Wondertoonel!

April 2005

Wondertoonel: an exhibition of curiosities or rarities. And currently, Mark Ryden's aptly named retrospective at the Pasadena Museum of California Art. This whimsical word poignantly encompasses Ryden's body of work - in itself a collection of curiosities - and subtly alludes to a surprisingly significant history. Ryden divulges the story of Wondertoonel in his artist's statement: Specifically, the word derives from Wondertoonel der Nature, a work from 1706 by Dutch merchant Levin Vincent, which featured etched images of his collection of mysterious and beautiful relics from the natural world. Furthermore, wondertoonel evokes the evolution of "wonder chambers" or wunderkammen of curiosities, like Vincent's, from early individual collections into the modern museum.

An avid collector of curiosities himself, it is no wonder that Ryden feels a connection to this history. In fact, Ryden identifies his vast collection as his primary source of artistic inspiration - a truth that is evident upon examining his body of work. Ryden's works are populated by a mysterious language of objects, symbols, animals, and allusions ranging from alchemy and fairy tales to Buddhism and the Bible.

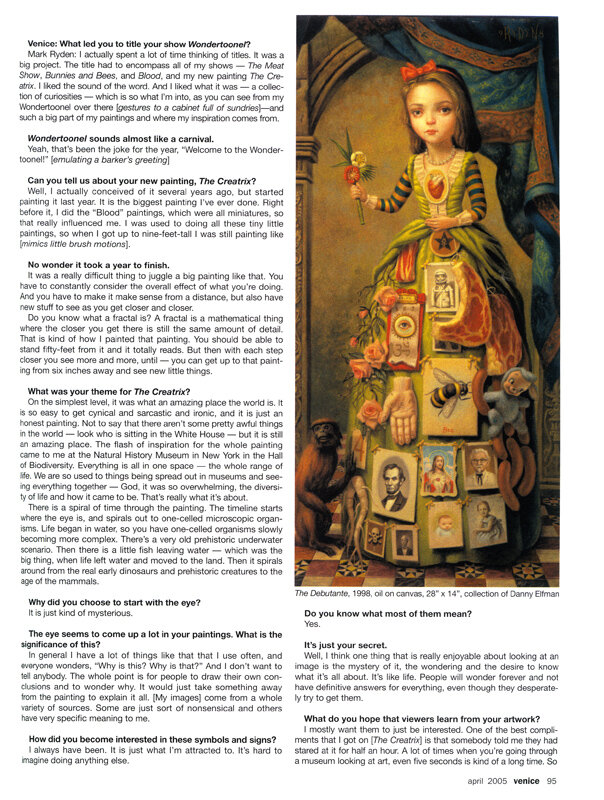

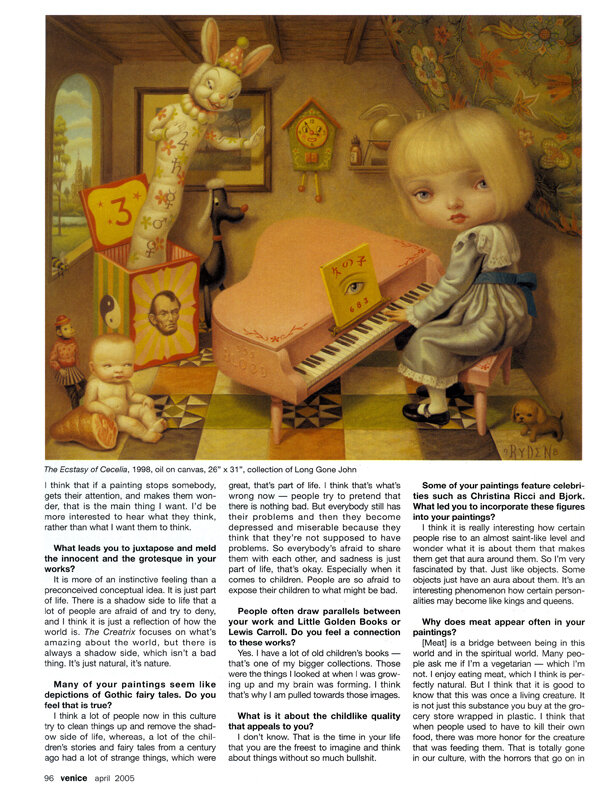

At first glance, many of Ryden's works seem to depict candycolored children's tales - wide-eyed prepubescent girls and bunnies abound in a world where Barbie is Saint and Lincoln still President. Upon closer examination, one seems to have been transported to a veritable warped Wonderland (Alice and the White Rabbit included), or perhaps a twisted playground, where a giant skull becomes a jungle gym.

There is something both uncanny and demure about the unflappable children in Ryden's works. Even when surrounded by slabs of meat and a bizarre freak show of toys gone mad, these children stare, provocatively aloof, out of his sinister fantasy world. Is this a commentary on a generation of children so overwhelmed by the proliferation of commodification and violence that it fails to disturb them? Ryden remains elusive, noting only that this disconcerting juxtaposition reflects the "shadow side" of life.

Drawing on sources from Ingres and Bosch to Miro and Dali, Ryden's paintings combine a contemporary sensibility with classic form and technique, their flawless gleaming veneers further masking the mysteries locked within.

Raised in Southern California, Ryden received a Bachelor of Fine Art from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. He penetrated the art world as an illustrator and commercial artist, gaining prominence as he designed album covers for the likes of the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Michael Jackson (including Jackson's Dangerous album). His works are now collected worldwide and may be found amongst the possessions of celebrities such as Leonardo DiCaprio, Stephen King, Bridget Fonda, and Ringo Starr.

Ryden is often reticent to reveal the intended significance of his paintings, with their complex compositions and rich imagery, leaving his viewers to their own interpretations. Venice recently had a rare opportunity to visit Ryden at his home and delve into the mind of this mysterious artist.

Venice: What led you to title your show Wondertoonel?

Mark Ryden: I actually spent a lot of time thinking of titles. It was a big project. The title had to encompass all of my shows - The Meat Show, Bunnies and Bees, and Blood, and my new painting The Creatrix. I liked the sound of the word. And I liked what it was - a collection of curiosities - which is so what I'm into, as you can see from my Wondertoonel over there \gestures to a cabinet full of sundries]-and such a big part of my paintings and where my inspiration comes from.

Wondertoonel sounds almost like a carnival.

Yeah, that's been the joke for the year, "Welcome to the Wondertoonel!" [emulating a barker's greeting]

Can you tell us about your new painting, The Creatrix?

Well, I actually conceived of it several years ago, but started painting it last year. It is the biggest painting I've ever done. Right before it, I did the "Blood" paintings, which were all miniatures, so that really influenced me. I was used to doing all these tiny little paintings, so when I got up to nine-feet-tall I was still painting like [mimics little brush motions].

No wonder it took a year to finish.

It was a really difficult thing to juggle a big painting like that. You have to constantly consider the overall effect of what you're doing. And you have to make it make sense from a distance, but also have new stuff to see as you get closer and closer. Do you know what a fractal is? A fractal is a mathematical thing where the closer you get there is still the same amount of detail. That is kind of how I painted that painting. You should be able to stand fifty-feet from it and it totally reads. But then with each step closer you see more and more, until -you can get up to that painting from six inches away and see new little things.

What was your theme for The Creatrix?

On the simplest level, it was what an amazing place the world is. It is so easy to get cynical and sarcastic and ironic, and it is just an honest painting. Not to say that there aren't some pretty awful things in the world - look who is sitting in the White House - but it is still an amazing place. The flash of inspiration for the whole painting came to me at the Natural History Museum in New York in the Hall of Biodiversity. Everything is all in one space - the whole range of life. We are so used to things being spread out in museums and seeing everything together - God, it was so overwhelming, the diversity of life and how it came to be. That's really what it's about. There is a spiral of time through the painting. The timeline starts where the eye is, and spirals out to one-celled microscopic organisms. Life began in water, so you have one-celled organisms slowly becoming more complex. There's a very old prehistoric underwater scenario. Then there is a little fish leaving water - which was the big thing, when life left water and moved to the land. Then it spirals around from the real early dinosaurs and prehistoric creatures to the age of the mammals.

Why did you choose to start with the eye?

It is just kind of mysterious.

The eye seems to come up a lot in your paintings. What is the significance of this?

In general I have a lot of things like that that I use often, and everyone wonders, "Why is this? Why is that?" And I don't want to tell anybody. The whole point is for people to draw their own conclusions and to wonder why. It would just take something away from the painting to explain it all. [My images] come from a whole variety of sources. Some are just sort of nonsensical and others have very specific meaning to me.

How did you become interested in these symbols and signs?

I always have been. It is just what I'm attracted to. It's hard to imagine doing anything else.

Do you know what most of them mean?

Yes.

It's just your secret.

Well, I think one thing that is really enjoyable about looking at an image is the mystery of it, the wondering and the desire to know what it's all about. It's like life. People will wonder forever and not have definitive answers for everything, even though they desperately try to get them.

What do you hope that viewers learn from your artwork?

I mostly want them to just be interested. One of the best compliments that I got on [The Creatrix] is that somebody told me they had stared at it for half an hour. A lot of times when you're going through a museum looking at art, even five seconds is kind of a long time. So I think that if a painting stops somebody, gets their attention, and makes them wonder, that is the main thing I want. I'd be more interested to hear what they think, rather than what I want them to think.

What leads you to juxtapose and meld the innocent and the grotesque in your works?

It is more of an instinctive feeling than a preconceived conceptual idea. It is just part of life. There is a shadow side to life that a lot of people are afraid of and try to deny, and I think it is just a reflection of how the world is. The Creatrix focuses on what's amazing about the world, but there is always a shadow side, which isn't a bad thing. It's just natural, it's nature.

Many of your paintings seem like depictions of Gothic fairy tales. Do you feel that is true?

I think a lot of people now in this culture try to clean things up and remove the shadow side of life, whereas, a lot of the children's stories and fairy tales from a century ago had a lot of strange things, which were great, that's part of life. I think that's what's wrong now - people try to pretend that there is nothing bad. But everybody still has their problems and then they become depressed and miserable because they think that they're not supposed to have problems. So everybody's afraid to share them with each other, and sadness is just part of life, that's okay. Especially when it comes to children. People are so afraid to expose their children to what might be bad.

People often draw parallels between your work and Little Golden Books or Lewis Carroll. Do you feel a connection to these works?

Yes. I have a lot of old children's books - that's one of my bigger collections. Those were the things I looked at when I was growing up and my brain was forming. I think that's why I am pulled towards those images.

What is it about the childlike quality that appeals to you?

I don't know. That is the time in your life that you are the freest to imagine and think about things without so much bullshit.

Some of your paintings feature celebrities such as Christina Ricci and Bjork. What led you to incorporate these figures into your paintings?

I think it is really interesting how certain people rise to an almost saint-like level and wonder what it is about them that makes them get that aura around them. So I'm very fascinated by that. Just like objects. Some objects just have an aura about them. It's an interesting phenomenon how certain personalities may become like kings and queens.

Why does meat appear often in your paintings?

[Meat] is a bridge between being in this world and in the spiritual world. Many people ask me if I'm a vegetarian - which I'm not. I enjoy eating meat, which I think is perfectly natural. But I think that it is good to know that this was once a living creature. It is not just this substance you buy at the grocery store wrapped in plastic. I think that when people used to have to kill their own food, there was more honor for the creature that was feeding them. That is totally gone in our culture, with the horrors that go on in slaughterhouses. It makes me want to become a vegetarian, but I enjoy eating meat too much.

Your paintings all have a very flawless finish. Have you always painted in this style?

I've always painted pretty tight and realistic. Sometimes I almost feel like I'm a photographer, setting up a scene and taking a photograph of it - except it's going to be a painting. I've never been interested in heavy painting techniques. It is a whole different area of interest to really get into brush strokes and all that - which I can appreciate, but I'm really not interested in doing myself.

How do you think that growing up in the sixties and seventies influenced your art?

Well the first ten, fifteen years of your life you learn about the world and the archetypes of life are introduced to you, then that is how your brain is formed and those symbols and things are so much a part of the time that you grow up in. So when I think about it, I was looking at Salvador Dali and Magritte. Their brains were formed fifty years earlier. When I think of somebody young looking at my art now, it's just a chain reaction. During the sixties there was just an explosion of pop culture, comic books, and art that combine together as a whole visual array to work with.

You once mentioned that you are fascinated by alchemy.

Many people think of alchemy as the beginning of chemistry, when they were trying to turn lead into gold. That's not really what alchemy was about. It was about studying the mysteries of life and trying to bridge the physical world and the spiritual world. That's what inspires me to make art.

Who are some of your favorite artists and why?

I like, of course, Bosch and the content of his work - the mysterious quality of where the stuff comes from. David, for composition and painting technique. Ingres. A lot of the classical artists. Bouguereau, who paints flesh better than any other artist.

Your work is sometimes categorized as "Lowbrow" art. Do you agree with that association?

That's a big topic. It's really interesting. There is definitely something going on in the art world right now, and there is a reaction to this - what has now become very closed, old art world that's been going on for fifty years in New York, and everybody's bored of it. There is this vital thing going on - a lot of it is outside of New York and here in Los Angeles. A lot of people call it Lowbrow. Juxtapoz magazine is a big part of it. Within it there are so many different kinds of art. There is this whole tattoo, hot-rod culture that I feel no connection to, but there are definitely all these other artists that I do feel a connection to - like Marion Peck and Eric White. There is definitely something going on. I don't know if it's lowbrow. Nobody's come up with a really good name for it yet.

How would you describe "Lowbrow" art?

[Lowbrow] seems to be artwork that values the image as opposed to just the concept. In the "highbrow" art world, it's completely a negative to use skill in painting, to make the painting of an image interesting to look at.

Not to be biased.

Right. [laughs] And I think that's what connects all of our pieces - loving imagery, in addition to concept and content.