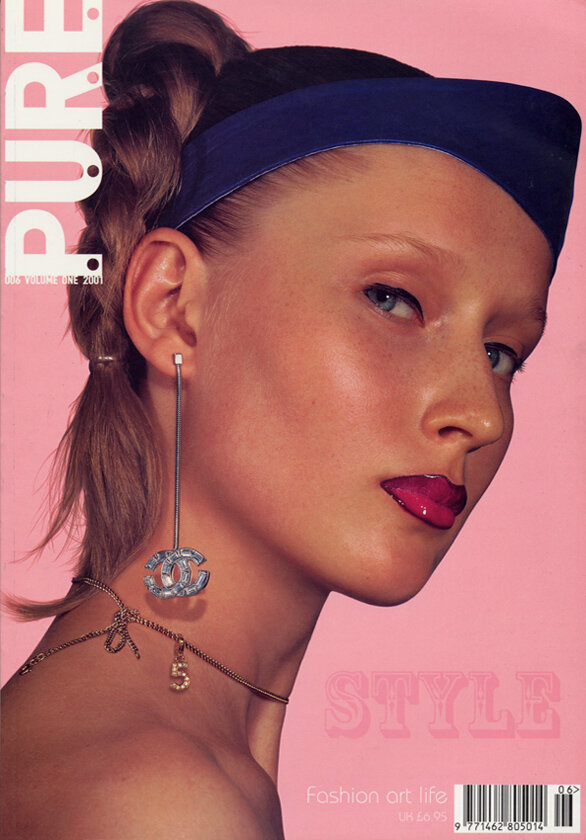

PURE Magazine

No. 006, Vol One, 2001

The Meat Alchemist

By Noko

His fans includes the likes of Robert DeNiro, Leonardo DiCaprio, Stephen King and Michael Jackson. Painter Mark Ryden talks to Noko about his predilection for Christina Ricci, Abe Lincoln, prime beef and his little friend the Magic Monkey

Call me old fashioned, but I like paintings. It all started for me when, as a child, my grandmother took me to Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery. Home of the finest 19th Century Symbolist / Pre-Raphaelite collection outside London or Paris. As I approached the grand stairway, I was completely overwhelmed by the vast canvas I saw towering above me: "Samson and Delilah" by Solomon Solomon (1887). The sheer epic power-chord emotional scale and dramatic angst of it all won me over to the power of paint... forever.

Painters and painting have been out of fashion for a while now. Personally, I blame Marcel Duchamp. Ever since that guy descended the staircase, and began taking the piss in someone else's urinal, the thought of actually representing stuff has seemed like the intellectually poor hick-cousin of Conceptual art.

The upshot of this is that, here in the UK, the difference between the Turner prize and the Edinburgh festival gets smaller and smaller every year, and far from being the new Rock' n' Roll, BritArt has degenerated into the new alternative comedy. Don't get me wrong, there is, and always will be a place for good conceptual art - Jenny Holzer, Andres Serrano, Thomas Grunfeld, Marc Quinn and Damien Hirst consistently hit the same eternal primordial highs that Bronzino, Bosch and Bacon did, it's just all the mediocre shite we have to wade through on route.

Often included lazily in the roster of US artists that make up the Lowbrow Art "movement" (post-Robert Williams / Ed Roth representational "outsider" artists currently beginning to crack the "Fine-Art" gallery circuit in Los Angeles), Mark Ryden's work can broadly be described as a kind of pop-art surrealism with a non-linear-kind-of-post-modern-matrixing, that could have only come from one born in the 60's and raised in Southern California on simply too much of everything they put in the water, the meat and the TV over there.

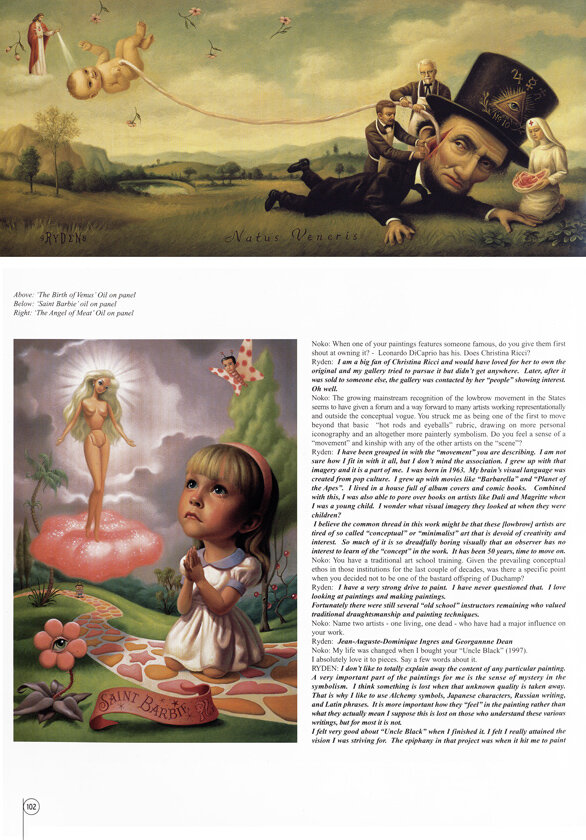

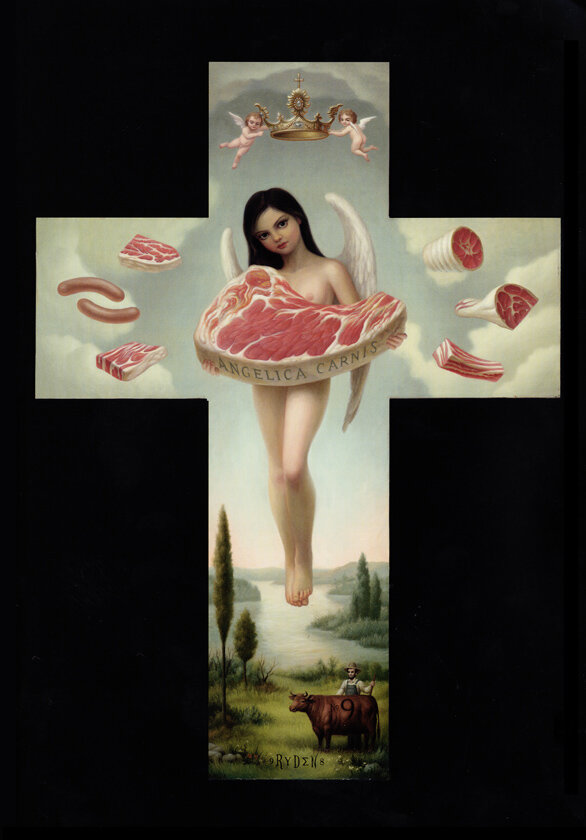

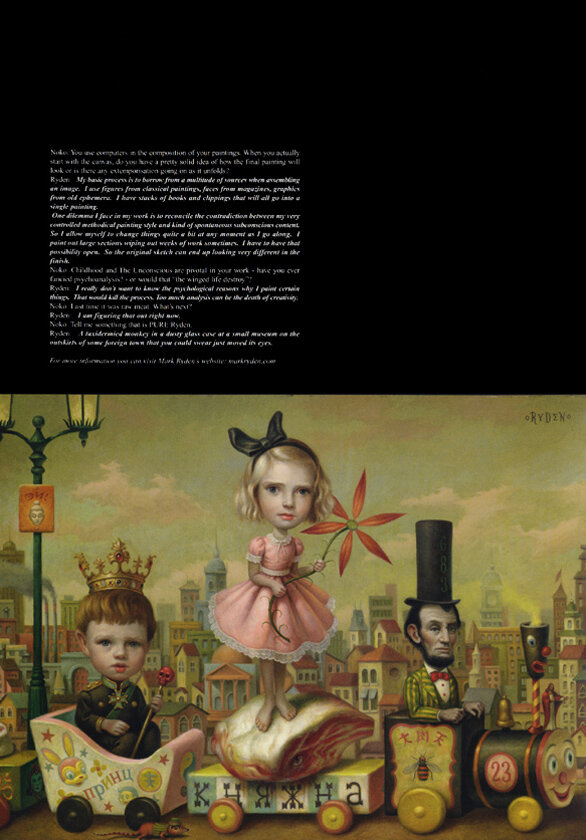

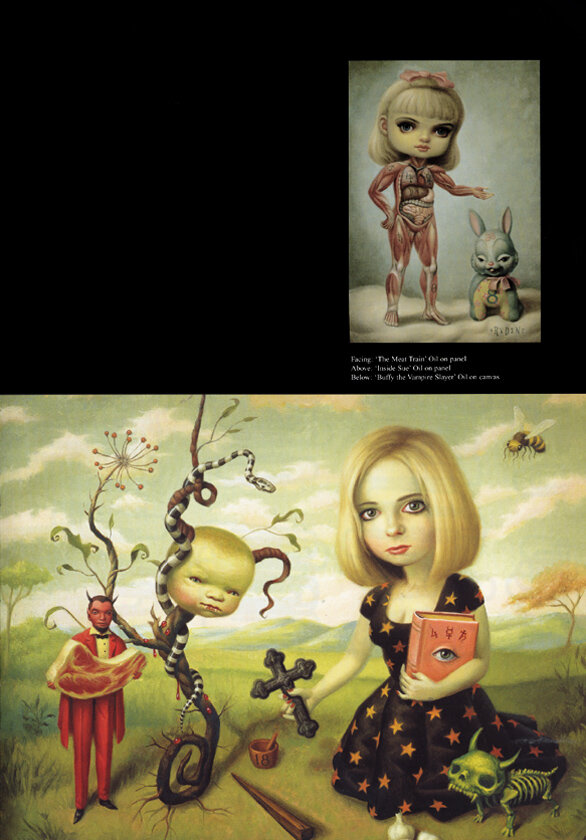

Ryden's paintings have such an intensely consistent portfolio of personal iconography that you could virtually write a Rule-book or Users' Guide on it. They are filled with dewy-eyed dream children with engorged heads, in a strange and empowering limbo between absolute innocence and world-weariness; a Pandora's box of toys of both now and bygone ages, benign beasts both real and mythical: Abe Lincoln, Hollywood actors, rock stars, spaceships, ancient medical equipment, Colonel Sanders and raw meat.

The subjects of his paintings exist in perfect out-of-proportion half-remembered Lewis Carroll playrooms or primordial prehistoric landscapes littered with the exotic symbols tied to Alchemy, freemasonry, the mystic Orient and the everyday imprint of TV advertising. The thing that somehow ties these seemingly disparate images together, is simply the paint. Ryden's touch sings with an even-handed celebration of Art history from High to Low, Ingres to Margaret Keane, Redon to Rivera, 40's wildlife illustrators to 60's Psychedelia. Ryden has claimed that it is in fact not he who paints these paintings, but a magic monkey who comes to visit him late at night.

Noko: Do you ever worry that the magic monkey might start repeating himself, find someone else to visit, or worse still just sit there masturbating like a regular monkey?

Ryden: For me that is the core aspect of my work. I try and figure out how, to facilitate that creative feeling where you sense you are tapping into something more than yourself. It is very difficult to reach that state a lot of the time. When I was younger I never questioned it and creativity seemed limitless. Now I do have days where it is very difficult to get away from a very linear logical uncreative state mind.

Noko: Going back as far as Warhol, there appears to be an American work-ethic with guys who have come to prominence via an illustration background that puts the English "Artschool-dance-that-goes-on-forever" ethos to shame. Your commercial work: a positive influence or a hindrance to your creative life?

Ryden: It has mostly been a positive influence but there is both a positive side and a negative side. The most rewarding part of commercial work is the mass reproduction and the large audience you reach. The most overwhelming negative is the concessions you might have to take with a painting. Sometimes, computer manipulations can be made to your work after you are finished without you ever knowing. That can feel like a terrible violation.

Noko: One of your most famous images is undoubtedly Michael Jackson's "Dangerous" LP sleeve artwork - tell us something we don't know about the King of Pop

Ryden: I suppose the thing most people don't know, and what surprised me, was how "normal" Michael Jackson was in person. His public image is so strange I did not know what to expect but when I met with him we had a very typical and relaxed conversation. We had many common interests we talked about. Maybe I am just a freak also.

Noko: When one of your paintings features someone famous, do you give them first shout at owning it? - Leonardo DiCaprio has his. Does Christina Ricci?

Ryden: I am a big fan of Christina Ricci and would have loved for her to own the original and my gallery tried to pursue it but didn't get anywhere. Later, after it was sold to someone else, the gallery was contacted by her "people" showing interest. Oh well.

Noko: The growing mainstream recognition of the lowbrow movement in the States seems to have given a forum and a way forward to many artists working representationally and outside the conceptual vogue. You struck me as being one of the first to move beyond that basic "hot rods and eyeballs" rubric, drawing on more personal iconography and an altogether more painterly symbolism. Do you feel a sense of a "movement" and kinship with any of the other artists on the "scene"?

Ryden: I have been grouped in with the "movement" you are describing. I am not sure how I fit in with it all, but I don't mind the association. I grew up with that imagery and it is a part of me. I was born in 1963. My brain's visual language was created from pop culture. I grew up with movies like "Barbarella" and "Planet of the Apes". I lived in a house full of album covers and comic books. Combined with this, I was also able to pore over books on artists like Dali and Magritte when I was a young child. I wonder what visual imagery they looked at when they were children? I believe the common thread in this work might be that these [lowbrow] artists are tired of so called "conceptual" or "minimalist" art that is devoid of creativity and interest. So much of it is so dreadfully boring visually that an observer has no interest to learn of the "concept" in the work It has been 50 years, time to move on.

Noko: You have a traditional art school training. Given the prevailing conceptual ethos in those institutions for the last couple of decades, was there a specific point when you decided not to be one of the bastard offspring of Duchamp?

Ryden: I have a very strong drive to paint. I have never questioned that I love looking at paintings and making paintings. Fortunately there were still several "old school" instructors remaining who valued traditional draughtsmanship and painting techniques.

Noko: Name two artists - one living, one dead - who have had a major influence on your work.

Ryden: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Georgannne Dean

Noko: My life was changed when I bought your "Uncle Black" (1997). I absolutely love it to pieces. Say a few words about it.

RYDEN: I don't like to totally explain away the content of any particular painting. A very important part of the paintings for me is the sense of mystery in the symbolism. I think something is lost when that unknown quality is taken away. That is why I like to use Alchemy symbols, Japanese characters, Russian writing, and Latin phrases. It is more important how they 'feel" in the painting rather than what they actually mean I suppose this is lost on those who understand these various writings, but for most it is not. I felt very good about "Uncle Black" when I finished it. I felt I really attained the vision I was striving for. The epiphany in that project was when it hit me to paint.

Noko: You use computers in the composition of your paintings. When you actually start with the canvas, do you have a pretty solid idea of how the final painting will look or is there any extemporisation going on as it unfolds?

Ryden: My basic process is to borrow from a multitude of sources when assembling an image. I use figures from classical paintings, faces from magazines, graphics from old ephemera. I have stacks of books and clippings that will all go into a single painting. One dilemma I face in my work is to reconcile the contradiction between my very controlled methodical painting style, and kind of spontaneous subconscious content. So I allow myself to change things quite a bit at any moment as I go along. I paint out large sections wiping out weeks of work sometimes. I have to have that possibility open. So the original sketch can end up looking very different in the finish.

Noko: Childhood and The Unconscious are pivotal in your work - have you ever fancied psychoanalysis? - or would that "the winged life destroy"'?

Ryden: I really don't want to know the psychological reasons why I paint certain things. That would kill the process. Too much analysis can be the death of creativity.

Noko: Last time it was raw meat. What's next?

Ryden: I am figuring that out right now.

Noko: Tell me something that is PURE Ryden.

Ryden: A taxidermied monkey, in a dusty glass case at a small museum on the outskirts of some foreign town that you could swear just moved its eyes.