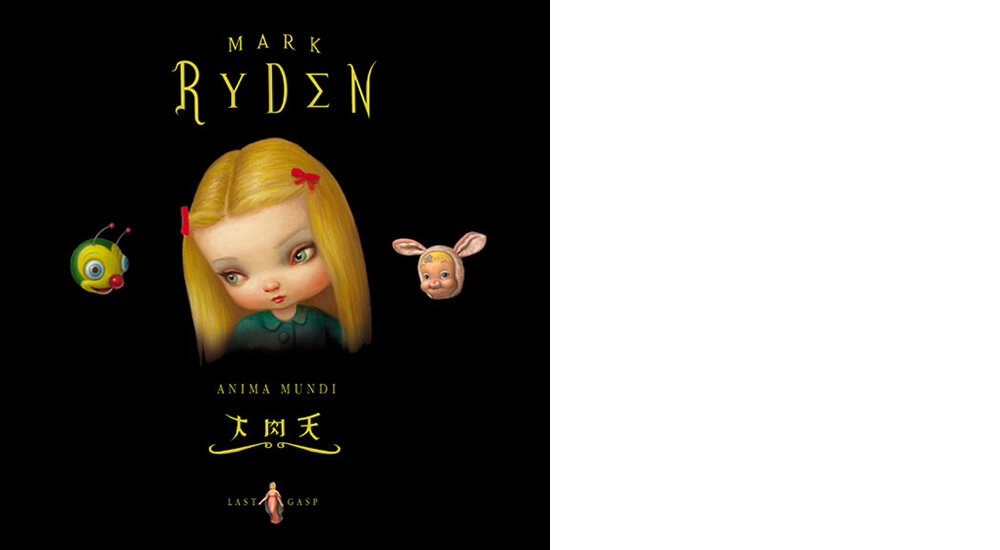

Anima Mundi

At Play in the Slaughterhouse of American Pop

Essay by Carlo McCormick

Publisher: Last Gasp / San Francisco, California

2001

Confronting the seamless contradictions and provocative absurdities of Mark Ryden’s paintings, the question hardly seems to be how does he think of this stuff, so much as why do they somehow make sense to us? As to the former question, this artist is far too imbued with the mystery to look for the reasons, and would rather attribute the radical extremes of his imagery to the convoluted choreography of those leaps of imagination that lie outside the bounds of intentionality. He’ll call it all a dream, what we might think of rather as some lucid dream-state where Ryden can access his subconscious without filters of forethought or the constructs of analysis. As to this latter question however, we cannot answer for the method to his madness without in some way coming to terms with the collective derangement of visual language and meaning that is endemic to our cultural schizophrenia as a whole. In the lineage of visionary art, reality has been twisted and pulled, inverted and turned inside out, for any number of reasons. Today, considering the pictures of Mark Ryden, it seems quite possible that such contortions of content and context here may be as much an idiosyncratic inventory of this painter’s private obsessions as it is some baroque symptomology for the greater public folly unleashed by a consumer media spectacle run amok.

Force fed on the obsessive compulsive diet of carnal indulgence and candy-coated junk that is America’s great contribution to the history of bad taste, Mark Ryden expels it all from the gut, giving gastric voice to the soft-white underbelly of our manic materialism, and heaving forth the bile and the beauty of our frothy fantasies back into the great vomitorium of popular culture. And make no mistake about it, this is a thoroughly American form of art-making. Evident not simply in the iconography, a language so easy to mimic now that it approaches universal familiarity, but in our national vernacular of conjunction, Ryden grasps at a tradition of mass communication in which the linearity of pictures has been forfeited for the sake of a highly articulated form of visual compression. His insistent manner of pastiche owes as much to the Surrealists as it does to the formal appropriation of their strategies by the world of advertising. The historical confluence is of course unmistakably post-modern. What is not post-modern per se, what is elusively yet unmistakably that which we would have to call Ryden’s Southern Californian sensibility, is the application of an irony that in no way constitutes a critique. If it is dark, it is still bathed in an unrelenting sunlight. If it is morbid, it still throbs with life. If it is perverse, it is so with such an unmitigated innocence that we must attribute this to our own dirty minds. Yes, Mark Ryden invites us into a slaughterhouse disguised as a madhouse, but it is also a funhouse, where the distortions of flesh and mind are there primarily for our greater entertainment.

No fairy tale is ever worth its weight in pixie dust if it doesn’t scare you just a little bit. Mark may not deliver the usual troupes of ogres, trolls and wicked witches, but his Never Never land has that velvet touch of evil none the less. Oddly, this most obvious aspect of Ryden’s art is in fact its most subtle as well. We may be well used to seeing skulls and devils in the work of Ryden’s contemporaries, but the context here is quite different. Mark Ryden does not celebrate evil, even in its most campy denatured form. Quite to the contrary, his art-making can be seen as an elaborate charade of avoidance towards life’s grimmer realities. His is an utterly pure infantilistic escapism. This is the artist’s gaze fixedly upon the sweet and shiny, the idealized and innocent, in deliberate denial of the more explicit alternatives. However, as in any emphatic effort to push the darker dimensions of experience out of sight and mind, in even Ryden’s most beautiful paintings something lingers, a shadow that haunts his nostalgia infused picturesque. For this artist, who also seeks to answer in his own way those big questions of life, what this dis-ease may ultimately amount to is an awareness of mortality.

In as much as Mark Ryden’s art is driven by startling and radical juxtapositions, none perhaps is as poignant and potent than the continued confrontation that takes place between the bucolic dream-scape of childhood and the innuendo of death. Much like the momento mori genre in which still lifes would be arranged in tableaus that would mimic the shape of a skull, Ryden’s pastoral is indeed a nature morte infused with the bitter-sweet reminder of how precious, ephemeral and fleeting youth and existence really is. This is obviously most evident in the skulls, skeletons and Christian religious imagery, but it is just as well true in its other myriad manifestations, from the head of Abraham Lincoln (a dour almost deathly expression of not simply an assassinated president but one of the first leaders to be captured in a photograph) to the ongoing leit-motif of meat. An admitted omnivore with no particular grudge against meat per se, Mark takes a certain relish in our whole consumer-culture of carnivores, particularly the cattle cross-section graphics and advertisements of those glory days in the 1950s before we worried about such petty matters of health and diet. For Ryden there is just something special about the depiction of a slaughtered carcass, the ways in which we package it to make us think of food rather than a murdered animal, the residue of our barbaric and primal past wrapped up in apron strings and the benevolent face of a smiling neighborhood butcher. With so much meat in these paintings, you know it’s not just random, perhaps more like some mythic metaphor akin to how the act of communion transmogrifies the cannibalistic act of ingesting the flesh and blood of Christ. But then again, it is also like all of Ryden’s visual obsessions, something that he does for no deeper reason than that he cannot resist it. Quite simply, Mark Ryden likes how meat looks, and damn, he can paint it better than anyone else I know.

For every aspect of Mark Ryden’s art, there is this split potential: on one hand the very simple explanation of his manic collector’s personality in which one or once could never be enough, and on the other a wealth of readings that one can take from or attach to his archetypal symbology. We might speculate ad nauseam on what the surface sexuality he allows his depictions of children to bare might tell about humanity, society and the artist, but would prefer to think of this as a kid’s book. So too is this artist’s contemplation of the ideals and artifacts our recent past, his true love and fanatical devotion to the halcyon days of popular Americana, open to all sorts of insights through cultural criticism. And then, while we’re at it, there are so many other ways in which the wealth of religious and art-historical references could be analyzed. But as much as one can sense how this is a painter who has taken some inspiration from the psycho-analytical legacy of Freud and Jung, he is certainly not parlaying in such currency himself. Mark Ryden has an uncanny access to the stuff that dreams are made of, and a rare capacity for sharing and baring the full glory of his explorations into this fantastical realm with us. His working process seems something of a waking dream state, a meditation on nothingness in which he can freely download all the surfeit of a life-time’s media overload. He does not try to explain his pictures, and I’m not sure that he even could. What Ryden shares is his passion for the mysterious and mystical sides of reality. When we questioned him about this visionary aspect of his art, he told us that he is in fact a pretty logical person, one who if not an artist might easily have chosen to become a mathematician. By such an account, we come to understand just how it is that the illogical fascinates him so. In it he may seek the discrete synchronicities and other-worldly perspectives that invisibly bind our chaotic world, and we can take pleasure in how this rational mind has turned its attention to the archetypal language of imagination itself.

—Carlo McCormick