Juxtapoz Magazine #161 - June, 2014

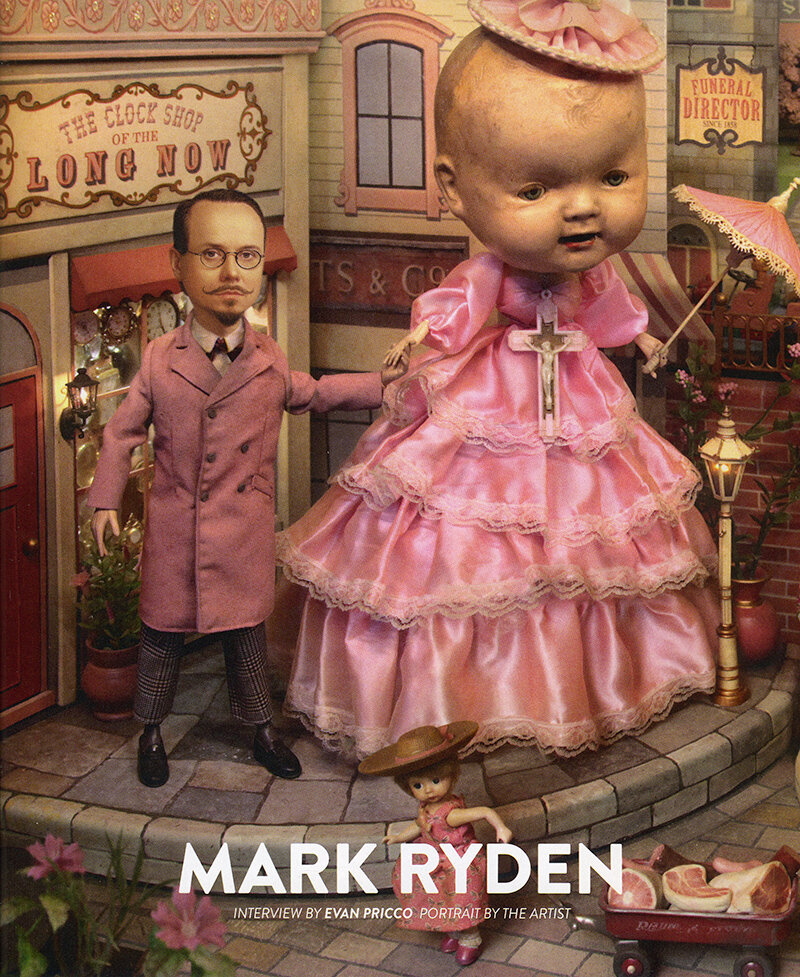

Mark Ryden – By Evan Pricco

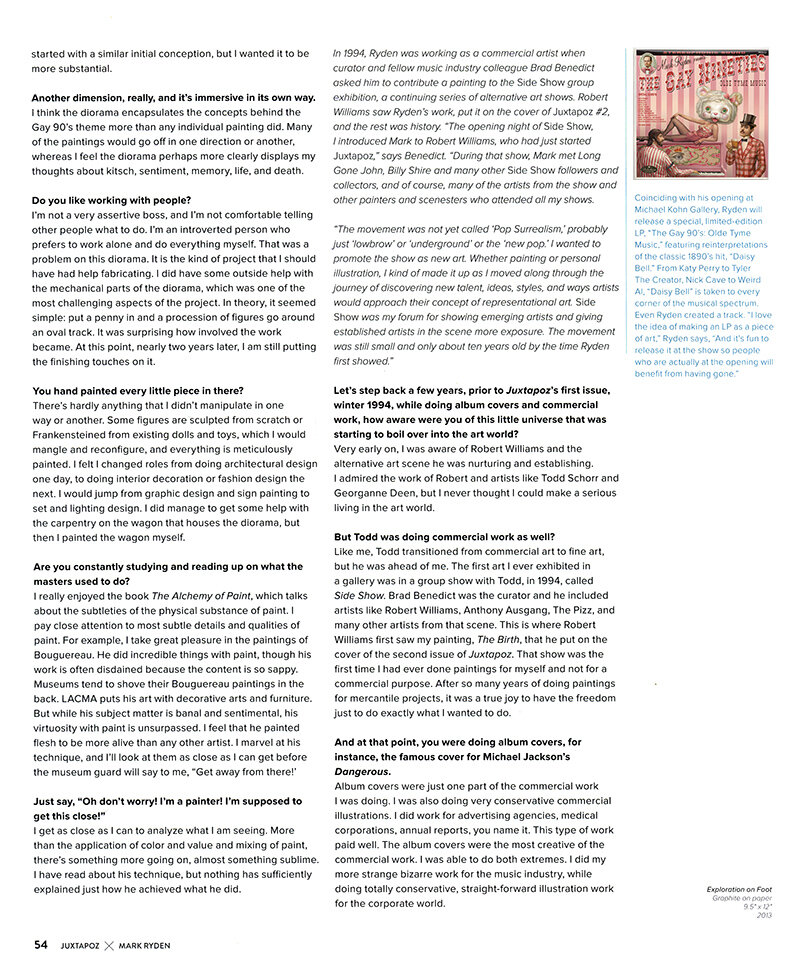

IT WASN'T SUPPOSED TO BE THIS WAY. It was all supposed to happen on November 11, 2011, just a quiet continuation of Mark Ryden's already blockbuster The Gay 90's Olde Tyme Art Show that showed in NYC at Paul Kasmin in Spring 2010. Mark was scheduled to work on a few new additions for the West Coast audience at Michael Kohn Gallery, have this one opening, then move on to another body of paintings slated for the near future.

"It wasn't going to be a grandiose show," Ryden tells me on a characteristically sunny winter day in Los Angeles, a few months before the still delayed The Gay 90's: West show was to open. "It was going to be just a smaller thing." Three and half years later, it's now become a big thing with bigger things. Let us explain.

In the world of outsider art. Mark Ryden is the "crossover hit." I love this phrase and wish I thought of it first. But it was Michael Kohn who coined the phrase to explain the phenomenon that is Ryden's collector cache and status as underground hero over the past two decades "What happened with me is probably what happens with most people when they encounter Mark's work," Kohn told me. "I was pretty amazed at how beautifully painted these works were, and how incredibly odd they were at the same time." And to be certain, Ryden is not the first artist who has made beautiful and odd work to find himself in the halls of the grand art fairs next to Warhols and Hirsts. Nor will he be the last. But in the 20 year history of Juxtapoz, few artists have captured the imagination quite like Ryden, a painter whose complex talent, sense of humor, and cultural appeal has seduced the fussiest critics into accepting that even in the much maligned world of Pop Surrealism, a new category can emerge: the populist blue chipper.

What makes the story even more interesting were the great odds that none of this was going to happen. If Brad Benedict didn't put Mark's first painting in Side Show in 1994, if Robert Williams didn't see that painting and put it on the cover of Juxtapoz #2, if Todd Schorr didn't make the leap from commercial to fine art, maybe Ryden wouldn't have had the confidence.

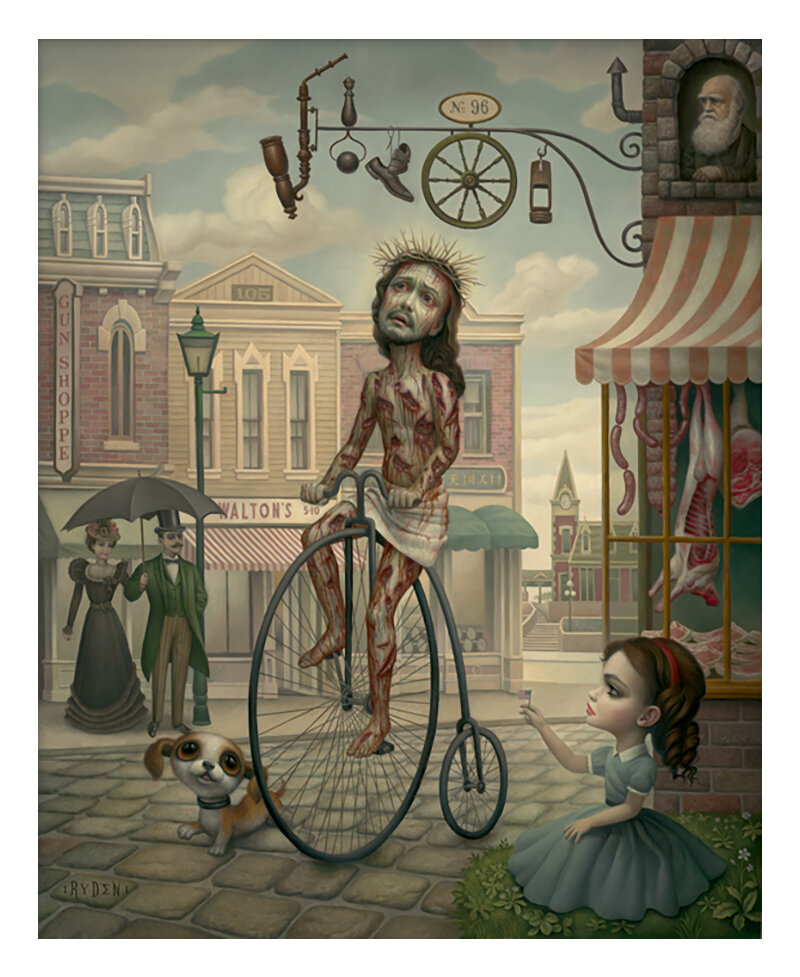

"Ryden is an heir apparent [to that first generation of comic book and outsider artists]," says Bolton Colburn, museum director and curator of the Laguna Art Museum Juxtapoz Factor retrospective in 2008. From the moment Ryden left commercial art behind in 1998 to the moment Kohn Gallery opens its renovated doors in 2014, Ryden has been sequestered in his studio, no need for assistants, a singular painter exploring what masters have done before and, in his case, transforming a love of Kitsch and Americana into figurative works of high and low culture. "There are a lot of artists who are gifted painters, technically, yet they're not as resonating as Mark," Kohn says. "And that means there's something else at work, besides his skill as a painter. His work is insidious because it's seductive, and at first glance, critics think its 'easy'... This unsettles them despite the fact that they like it."

Kirsten Anderson, who has shown Mark in the past as owner of Roq La Rue Gallery in Seattle, and instrumental in naming the genre Pop Surrealism, offered a direct take on Ryden's career. "I've never seen anything like it. I think he f's special," Anderson notes. "I think his success is due to many things all working in conjunction: one, he did happen to be there right as this art movement blew up, and second, he is a very canny businessman and he had a plan from the start in that I think he decided if he was going to play the art world game, he was going to go for it completely. Thirdly, and this is the most important, is that he does have the ability to capture the viewer in a way that very few do. You have a visceral reaction to a Ryden painting no matter what your opinion of it is. It's so purely what it is. He just can't be dismissed as any one thing. You can't deny his talent, and you can't denigrate him as 'big eye' or "kitsch" because he embraces it and transcends it."

"Ryden offers up the cloying artifice of Americana in perhaps its purest form since Norman Rockwell, and he manages to do so with such a stunning lack of camp and irony," art critic Carlo McCormick explained in describing the artist's trajectory and critical appeal. "He allows us to revel in our myths with the same suspended sense of make-believe that makes our folkloric exceptionalism so much fun."

There it is. Fun. So much fun. In asking over 20 people about Ryden, his career, and his art, fun came up over and over. In the art world of clean white walls, I assume fun has been a four-letter word for decades. Fun means that the art isn't taken seriously, yet with Ryden, there has been the serendipitous balance of unsurpassed technique, curiosity and fun in every painting he makes. In the midst of years of delays, Ryden created two masterworks, his biggest painting to date titled The Parlor, and an incredible hand-painted and constructed diorama that may be his most immersive fantasy to date. I spoke with Mark in two sessions at his home in Eagle Rock, California, on the eve of his first solo show in 4 years, 20 years since his first painting, and 19.5 years since his very first Juxtapoz cover.

Evan Pricco: Was this show always scheduled to open the new Michael Kohn space?

Mark Ryden: Originally this show was only going to be a simple continuation of The Gay 90's Olde Tyme Art Show. I did at Paul Kasmin Gallery in 2010.1 had more paintings I wanted to do around that theme, and I liked the idea of bringing back some of those paintings to the West Coast. It wasn't going to be a large scale show, but intended to be a smaller exhibition. It was originally scheduled to open 11/11/11 am interested in numerology and wanted to take advantage of that special date! As I began developing the show, Michael Kohn started renovating a new gallery space. It seemed like a great opportunity to have the premier show in his grand new space, so we delayed the exhibition... and that turned into three years of delays.

But in that time, did the show grow?

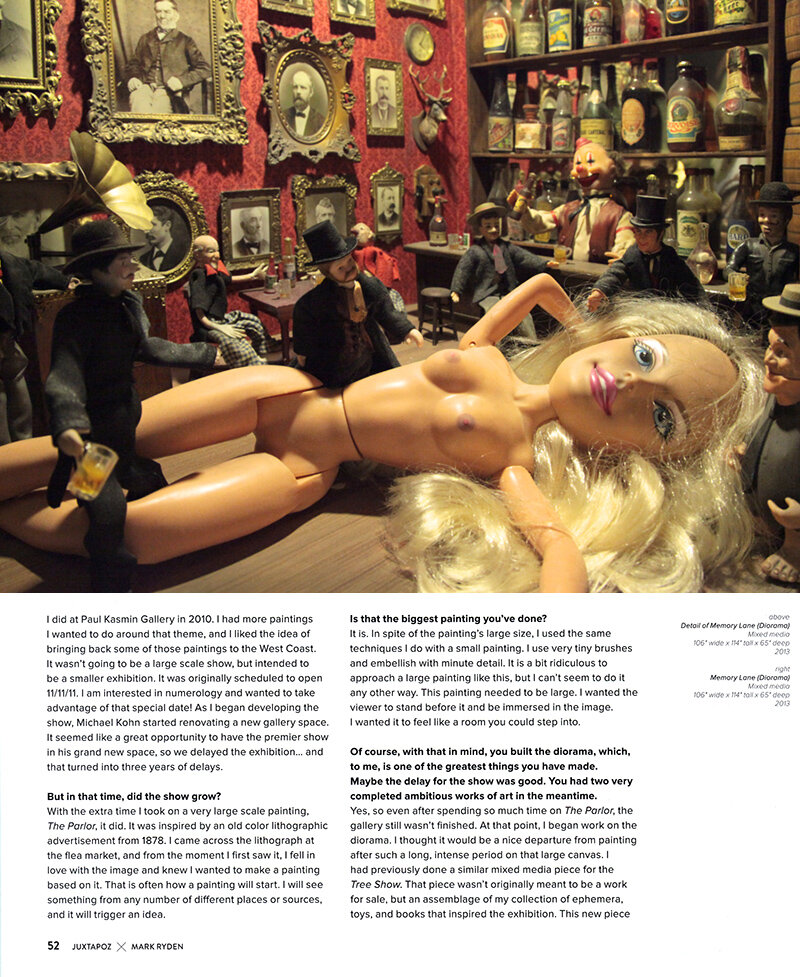

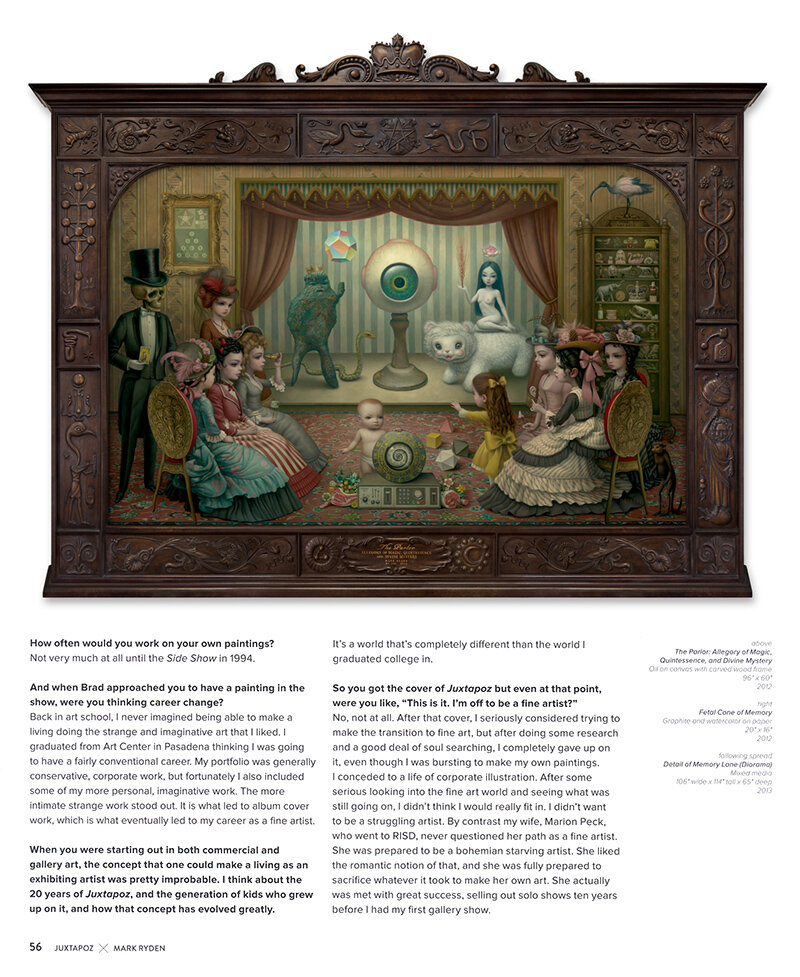

With the extra time I took on a very large scale painting, The Parlor, it did. It was inspired by an old color lithographic advertisement from 1878.1 came across the lithograph at the flea market, and from the moment I first saw it, I fell In love with the image and knew I wanted to make a painting based on it. That is often how a painting will start. I will see something from any number of different places or sources,

and it will trigger an idea.

Is that the biggest painting you've done?

It is. In spite of the painting's large size, I used the same techniques I do with a small painting. I use very tiny brushes and embellish with minute detail. It is a bit ridiculous to approach a large painting like this, but I can't seem to do It any other way. This painting needed to be large. I wanted the viewer to stand before it and be immersed in the image. I wanted it to feel like a room you could step into.

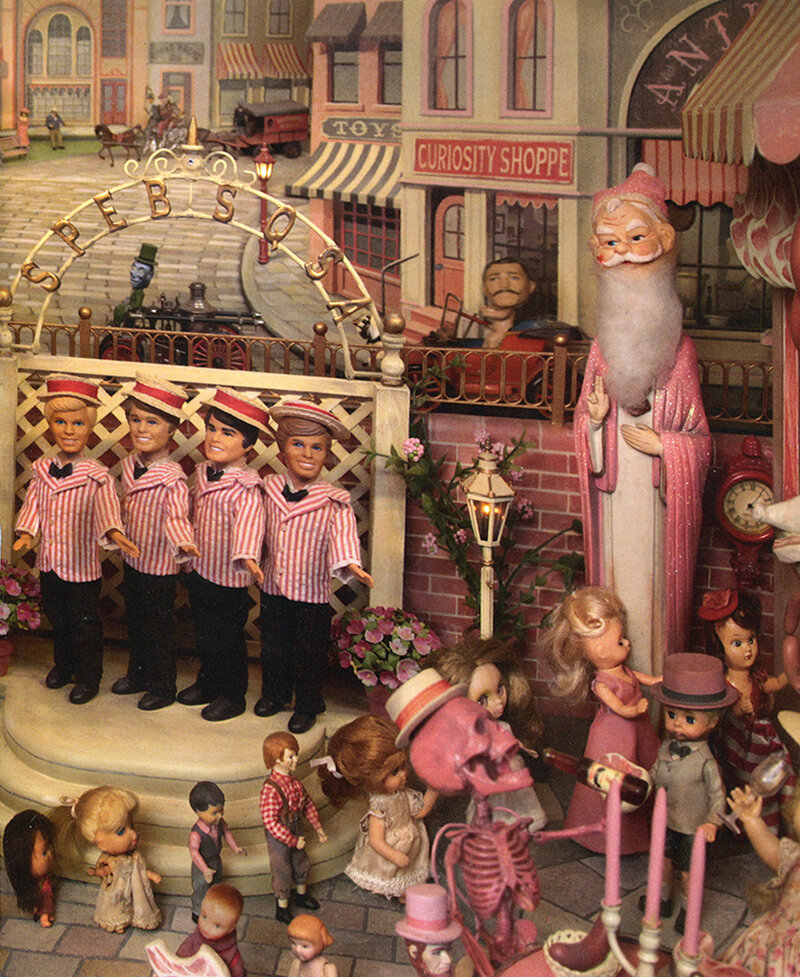

Of course, with that in mind, you built the diorama, which, to me, is one of the greatest things you have made. Maybe the delay for the show was good. You had two very completed ambitious works of art in the meantime.

Yes, so even after spending so much time on The ., .he gallery still wasn't finished. At that point, I began work on the diorama. I thought it would be a nice departure from painting after such a long, intense period on that large canvas. I had previously done a similar mixed media piece for the Tree Show. That piece wasn't originally meant to be a work for sale, but an assemblage of my collection of ephemera, toys, and books that inspired the exhibition. This new piece started with a similar initial conception, but I wanted it to be more substantial.

Another dimension, really, and it's immersive in its own way.

I think the diorama encapsulates the concepts behind the Gay 90's theme more than any individual painting did. Many of the paintings would go off in one direction or another, whereas I feel the diorama perhaps more clearly displays my thoughts about kitsch, sentiment, memory, life, and death.

Do you like working with people?

I'm not a very assertive boss, and I'm not comfortable telling other people what to do. I'm an introverted person who prefers to work alone and do everything myself. That was a problem on this diorama. It is the kind of project that I should have had help fabricating. I did have some outside help with the mechanical parts of the diorama, which was one of the most challenging aspects of the project. In theory, it seemed simple: put a penny in and a procession of figures go around an oval track. It was surprising how involved the work became. At this point, nearly two years later, I am still putting the finishing touches on it

You hand painted every little piece in there?

There's hardly anything that I didn't manipulate in one way or another. Some figures are sculpted from scratch or Frankensteined from existing dolls and toys, which I would mangle and reconfigure, and everything is meticulously painted. I felt I changed roles from doing architectural design one day, to doing interior decoration or fashion design the next. I would jump from graphic design and sign painting to set and lighting design. I did manage to get some help with the carpentry on the wagon that houses the diorama, but then I painted the wagon myself.

Are you constantly studying and reading up on what the masters used to do?

I really enjoyed the book The Alchemy of Paint, which talks about the subtleties of the physical substance of paint. I pay close attention to most subtle details and qualities of paint. For example, I take great pleasure in the paintings of Bouguereau. He did incredible things with paint, though his work is often disdained because the content is so sappy. Museums tend to shove their Bouguereau paintings in the back. LACMA puts his art with decorative arts and furniture. But while his subject matter is banal and sentimental, his virtuosity with paint is unsurpassed. I feel that he painted flesh to be more alive than any other artist. I marvel at his technique, and I'll look at them as close as I can get before the museum guard will say to me, "Get away from there!'

Just say, "Oh don't worry! I'm a painter! I'm supposed to get this close!"

I get as close as I can to analyze what I am seeing. More than the application of color and value and mixing of paint, there's something more going on, almost something sublime. I have read about his technique, but nothing has sufficiently explained just how he achieved what he did.

In 1994, Ryden was working as a commercial artist when curator and fellow music industry colleague Brad Benedict asked him to contribute a painting to the Side Show group exhibition, o continuing series of alternative art shows. Robert Williams saw Ryden's work, put it on the cover of Juxtapoz #2, and the rest was history. "The opening night of Side Show, / introduced Mark to Robert Williams, who had Just started Juxtapoz," soys Benedict, 'During that show, Mark met Long Gone John, Billy Shire and many other Side Show followers and collectors, and of course, many of the artists from the show and other painters and scenesters who attended all my shows.

"The movement was not yet called 'Pop Surrealism,' probably just 'lowbrow' or underground' or the 'new pop.' I wanted to promote the show os new art. Whether painting or personal illustration, I kind of made It up as I moved along through the journey of discovering new talent, ideas, styles, and ways artists would approach their concept of representational art. Side Show was my forum for showing emerging artists and giving established artists in the scene more exposure. The movement was still small and only about ten years old by the time Ryden first showed."

Let's step back a few years, prior to Juxtapoz's first issue, winter 1994, while doing album covers and commercial work, how aware were you of this little universe that was starting to boil over into the art world?

Very early on, I was aware of Robert Williams and the alternative art scene he was nurturing and establishing. I admired the work of Robert and artists like Todd Schorr and Georganne Deen, but I never thought I could make a serious living in the art world.

But Todd was doing commercial work as well?

Like me, Todd transitioned from commercial art to fine art, but he was ahead of me. The first art I ever exhibited in a gallery was in a group show with Todd, in 1994, called Side Show. Brad Benedict was the curator and he included artists like Robert Williams, Anthony Ausgang, The Pizz, and many other artists from that scene. This is where Robert Williams first saw my painting, The Birth, that he put on the cover of the second issue of Juxtapoz. That show was the first time I had ever done paintings for myself and not for a commercial purpose. After so many years of doing paintings for mercantile projects, it was a true joy to have the freedom just to do exactly what I wanted to do.

And at that point, you were doing album covers, for instance, the famous cover for Michael Jackson's Dangerous.

Album covers were just one part of the commercial work I was doing. I was also doing very conservative commercial illustrations. I did work for advertising agencies, medical corporations, annual reports, you name it. This type of work paid well. The album covers were the most creative of the commercial work. I was able to do both extremes. I did my more strange bizarre work for the music industry, while doing totally conservative, straight-forward illustration work for the corporate world.

How often would you work on your own paintings?

Not very much at all until the Side Show in 1994.

And when Brad approached you to have a painting in the show, were you thinking career change?

Back in art school, I never imagined being able to make a living doing the strange and imaginative art that I liked. I graduated from Art Center in Pasadena thinking I was going to have a fairly conventional career. My portfolio was generally conservative, corporate work, but fortunately I also included some of my more personal, imaginative work. The more intimate strange work stood out. It is what led to album cover work, which is what eventually led to my career as a fine artist.

When you were starting out in both commercial and gallery art, the concept that one could make a living as an exhibiting artist was pretty improbable. I think about the 20 years ofJuxtapoz, and the generation of kids who grew up on it, and how that concept has evolved greatly. It's a world that's completely different than the world I graduated college in.

So you got the cover of Juxtapoz but even at that point, were you like, "This is it. I'm off to be a fine artist?"

No, not at all. After that cover, I seriously considered trying to make the transition to fine art, but after doing some research and a good deal of soul searching, I completely gave up on it, even though I was bursting to make my own paintings. I conceded to a life of corporate illustration. After some serious looking into the fine art world and seeing what was still going on, I didn't think I would really fit in. I didn't want to be a struggling artist. By contrast my wife, Marion Peck, who went to RISD, never questioned her path as a fine artist. She was prepared to be a bohemian starving artist. She liked the romantic notion of that, and she was fully prepared to sacrifice whatever it took to make her own art. She actually was met with great success, selling out solo shows ten years before I had my first gallery show.

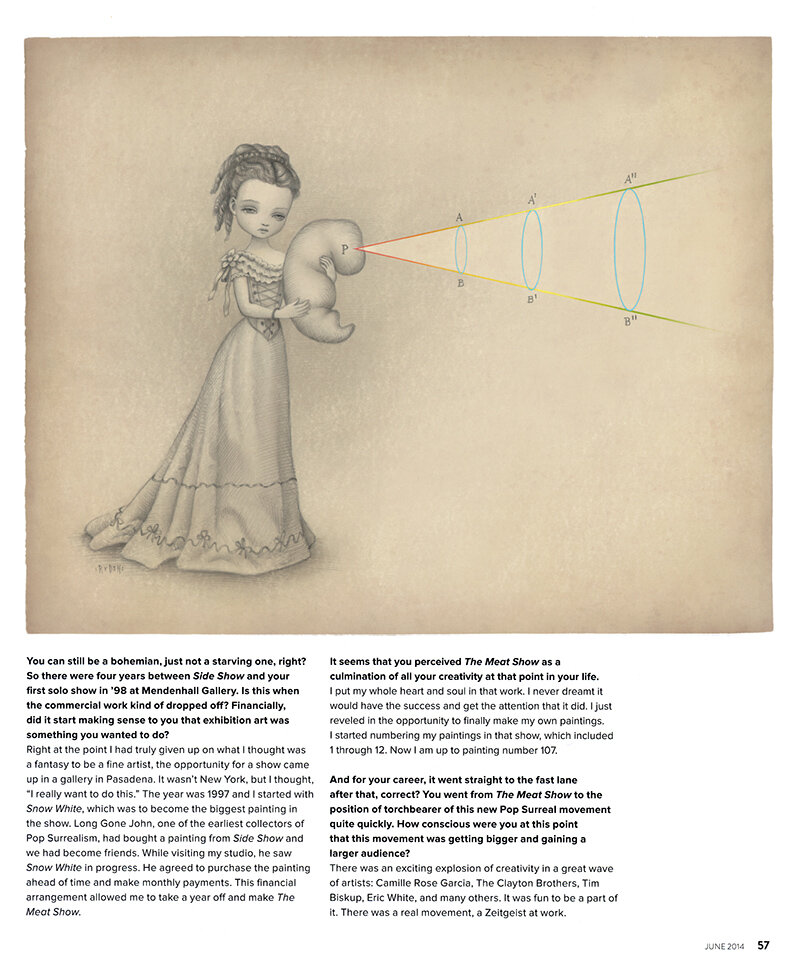

You can still be a bohemian, just not a starving one, right? So there were four years between Side Show and your first solo show in '98 at Mendenhall Gallery. Is this when the commercial work kind of dropped off? Financially, did it start making sense to you that exhibition art was something you wanted to do?

Right at the point I had truly given up on what I thought was a fantasy to be a fine artist, the opportunity for a show came up in a gallery in Pasadena. It wasn't New York, but I thought, "I really want to do this." The year was 1997 and I started with Snow White, which was to become the biggest painting in the show. Long Gone John, one of the earliest collectors of Pop Surrealism, had bought a painting from Side Show and we had become friends. While visiting my studio, he saw Snow White in progress. He agreed to purchase the painting ahead of time and make monthly payments. This financial arrangement allowed me to take a year off and make The Meat Show.

It seems that you perceived The Meat Show as a culmination of all your creativity at that point in your life.

I put my whole heart and soul in that work. I never dreamt it would have the success and get the attention that it did. I just reveled in the opportunity to finally make my own paintings. I started numbering my paintings in that show, which included 1 through 12. Now I am up to painting number 107.

And for your career, it went straight to the fast lane after that, correct? You went from The Meat Show to the position of torchbearer of this new Pop Surreal movement quite quickly. How conscious were you at this point that this movement was getting bigger and gaining a larger audience?

There was an exciting explosion of creativity in a great wave of artists: Camille Rose Garcia, The Clayton Brothers, Tim Biskup, Eric White, and many others. It was fun to be a part of it. There was a real movement, a Zeitgeist at work.

Have you always been someone who likes to have shows so spread out? Do you like to wait that two or three years?

I would actually prefer to have more frequent shows that were smaller in scale. I would like to explore more themes as well as make a larger number of smaller works. The pressure of building up a show for four years is stressful. I think about Michael Jackson's career versus Madonna's career. Michael had the number one record in the world, and after that, he felt he had to outdo himself every time. I think he was frozen by it. Madonna, on the other hand, just releases record after record. They're well received, some more than others, but she just keeps going. She doesn't have to be the top of all the charts with every single project she works on. That's a much better way to have a career. It allows for much more creativity and freedom.

With that said, with this new show, you're kind of MJ.

I suppose so, but I want to be Madonna.

How Ryden gets placed in the history books was a huge curiosity for everyone I spoke to in preparing for this piece. When I broached the subject with Bolton Colburn, he gave an expansive view. "I do know that this thing called Art History is fracturing, allowing for a much broader and inclusive interpretation of visual history and what is important in that history." Ryden's appreciation for history, politics, and museums was how we ended our conversation.

You have released many editions to raise money for organizations like The Nature Conservancy and the Sierra Club. Are you an environmentalist?

I care deeply about the environment. I think one of our most serious issues is our mistreatment of the earth.

Your shows are politically in tune, but not overt.

I don't consciously make my art with a political agenda. I didn't do The Tree Show because I'm an environmentalist. It was spiritually motivated, working with the divinity of nature. It's interesting to observe the disparity in how people look at nature. Some people will look at California's massive redwood trees and see evidence of God, while other people think "Let's chop 'em up and make lots of money." Looking at the earth as a commodity is destroying our planet.

Do you find it odd that this far into the Pop Surrealism movement, or figurative painting like this in general, that there's still a little bit of a prejudice?

Unfortunately, it still seems like the old guard continues to look down upon painting, and realism in particular. I was just reading about renovation plans at the MoMA in New York. They plan to make an addition with glass walls that you can't hang paintings on, so it's only going to show installations, sculptures, and performance video art. There's still a prejudice toward painting, I guess, as if they feel it's not possible to explore new ideas with the "dead" language of painting. I think that is a ridiculous notion.

Like it's antiquated. Is there a sense of pride that you can walkthrough the Basel fair and see one of your paintings?

It's interesting how out of place my work often looks in the context of a contemporary art fair. I am very lucky there are those in that world who do appreciate my work.

In 20 years from now, if you could have your art at an institution or on display, where would you like to see it?

There are a lot of reasons to reject the museum world and want nothing to do with it, but I honestly love these treasures. My favorite places to go are museums, whether they are fine art museums, museums of natural history, or museums of medical oddities. To me, they're like churches. A museum, when not too crowded, can be a place to leave behind the loud, busy world, and reverently stand before something inspirational and quietly contemplate it. I love the idea of my work being viewed in that context. I think the ultimate achievement would be to have my work in an institution like the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In a day and age of such mechanical reproduction, where everything is at your fingertips, where you can live vicariously through others, do you think that viewing an original piece of art still takes people back to a certain feeling?

I believe something spiritual happens in front of an original painting. You can feel something you would never get from a mechanical reproduction. This reminds me of my experience with Botticelli's The Birth of Venus. I never really cared for that painting when I had only seen it countless times in reproduction. But standing before the original, I just couldn't believe the feelings I got from it. I was enchanted.

How would you explain your work ethic in the totally simplest way possible?

I work very, very hard. I don't paint every day, but I work hard almost every day. There's a quote, "The harder I work, the better luck I have." I do think I've been very lucky, but I've worked so hard. I've always worked hard.

Mark Ryden's The Gay 90's: West opened at Michael Kohn Gallery in Los Angeles on May 3, 2014